Cinerama At the Plaza, Melbourne, Australia |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

|

Written

by: Eric White. Ross Thorne's pictures are from "Cinemas of Australia via U.S.A." ISBN 0 909425 22 1. |

Date: July 8, 2004 |

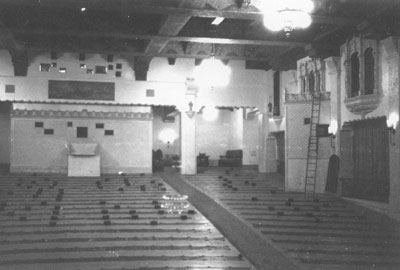

The

Plaza shortly after closure and the removal of the seats. (The objects on

the stage are parts of a chandelier). Photo credit, Wayne Brown. The

Plaza shortly after closure and the removal of the seats. (The objects on

the stage are parts of a chandelier). Photo credit, Wayne Brown.For twelve years, from 1958 until 1970, Cinerama was exhibited at Melbourne’s Plaza theatre. It was very popular in a period when the cinema business was struggling. The Plaza basked in the glow of this popularity. As the 1960’s progressed however, changing tastes in film and presentation meant that cinemas like the Plaza, and its big brother upstairs the Regent, were no longer needed. This is the story of the Plaza’s Cinerama period and its final days. In September 1952 Cinerama was first presented to movie audiences in New York. This huge-screened, audience-enveloping experience left the movie industry stunned and admiring at a time when mainstream movies were in decline. Quickly Hollywood sought to imitate it with cheaper wide-screen systems and spectacular subject matter. Meanwhile Cinerama opened in new locations and produced several new films in much the same travelogue style as its initial effort, "This Is Cinerama". By the latter part of the 1950s, the Cinerama phenomenon had settled down. Thee had been a steady expansion into the major cities of the United States, Canada, London, Europe and Japan, engineered by business deals with various partnerships. The original barn-storming entrepreneurs who had backed Cinerama had been almost completely replaced by more conservative owners due to the constant need to raise more capital to finance this expansion. It was now time for a methodical development of new venues through the rest of the world, including Australia. From 1953, the Stanley-Warner Corporation, primarily a lingerie manufacturer, had the rights to make and distribute Cinerama films and open theatres. It then entered into a partnership with Robin International and gave this company the right to open theatres in Britain, Europe and Japan. By the middle of 1955 there were 25 Cinerama theatres. In 1958 the agreement was extended to the rest of the world, except for a few countries where Stanley-Warner already had interests, which included Australia and Canada, Venezuela and Cuba. (It did them no good in Cuba. Castro expropriated the theatre and put in the Soviet version of Cinerama, Kinopanorama.) |

Further

in 70mm reading: in70mm.com's Cinerama page The Lost World of 70mm Theatres 70mm in Sydney Internet link: This article originally appeared in CINEMARECORD, published quarterly. It is the magazine of the Melbourne-based Cinema and Theatre Historical Society (Victoria) |

|

Cinerama was ready for a growth spurt. Several second-string U.S. locations had closed due to declining business and the slow production of new Cinerama movies. There was unused presentation equipment stored at Cinerama headquarters at Oyster Bay, Long Island and money could still be made from the early features, which had yet to be seen in many countries. The time was ripe for Cinerama to be established in Australia. Many Australian exhibitors had shown some interest in Cinerama since the middle 1950s, but their tentative proposals had not borne fruit. It was not until a Cinerama/Stanley-Warner representative Bruce Newbery came to Australia in 1957 to set up arrangements for the filming of the Australian sequence of Cinerama’s South Seas Adventure that the pace quickened. Stanley-Warner did a deal with Hoyts Theatres Ltd and in early 1958 it was announced that Cinerama theatres were to be established in Sydney and Melbourne within the year. Hoyts was well placed to introduce Cinerama. It had led the exhibition industry in introducing Cinemascope and drive-in theatres, was owned by industry giant Twentieth Century Fox and had prestigious cinemas in all Australia’s capital cities. Cinerama sent a representative to Australia to inspect possible sites for conversion. The manager of Melbourne’s Esquire in the late fifties remembers being told by the city supervisor, Reg Potter, to expect a visit. A rather physically unprepossessing but fast talking American, Harry Goldberg, turned up in due course and gave the Esquire the once over. Hoyts New Malvern was also briefly considered. It was decided that the Plaza was the best proposition for Cinerama however. The Sydney Plaza was also selected. |

|

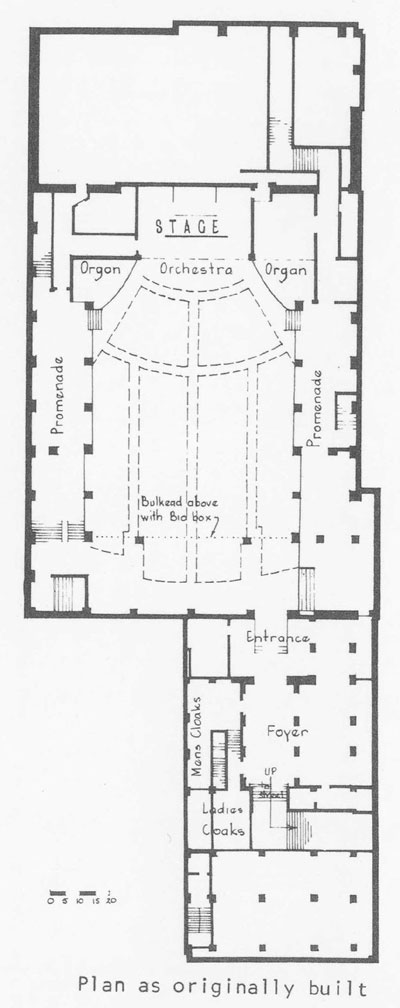

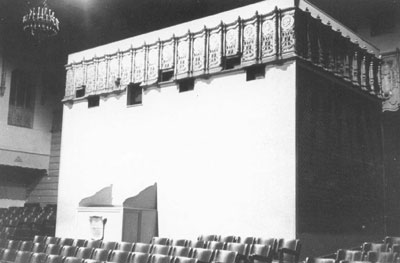

The

"Baker" and "Charlie" projection rooms, with the console operator's desk in

front and the original projection room above. Photo credit, Wayne Brown The

"Baker" and "Charlie" projection rooms, with the console operator's desk in

front and the original projection room above. Photo credit, Wayne BrownCinerama reserved the right to control the choice of theatres for an installation. The technical requirements were complicated. Only wide auditoriums with the capacity for horizontal projection would do. There could be little or no ‘rake’ as key-stone distortion of the picture had to be avoided. There also needed to be adequate height for the screen as well as width. The Sydney Plaza closed for renovation on Wednesday 3 September 1958, though preparatory work had been going on in the early mornings for some weeks. It re-opened two weeks later, equipped for Cinerama with the plant from a closed-down cinema at Miami Beach. Sydney was Cinerama’s 37th theatre opening. There was a grand charity premiere on Wednesday 17 September of This Is Cinerama. Cinerama was not to open in Melbourne until Boxing Day. The Melbourne Plaza closed for renovation on 22 October. The last program was "The Gift of Love" with Lauren Bacall and Robert Stack. The Plaza was Cinerama’s 40th theatre to open, but that does not mean that there were 40 cinemas operating at the end of 1958. Several had closed due to lack of new product. Only one new film per year was being produced, and many smaller U.S. cities could not sustain a twelve-month run. Hence there was a good supply of second hand equipment. Considerably more work was required for installing Cinerama at the Melbourne Plaza than in Sydney. Though it was Hoyts most suitable Melbourne theatre, there was not enough stage height for the screen, and only just enough width. The original proscenium height was about 17 feet (5.2m) and the new screen was to be 24 feet high (7.3m). Consequently the floor of the auditorium needed to be lowered, with a greater slope down to the stage. Three new projection rooms, with their own ventilation system, had to be constructed. Only then could the screen and projection gear be installed. |

|

The

Able projection room, recessed into the promenade area. Photo credit, Wayne

Brown. The

Able projection room, recessed into the promenade area. Photo credit, Wayne

Brown.The costs of structural alterations had to be borne by the theatre proprietor. It was stated by Roberts Dunstan, the Herald’s film critic, that the cost of the conversion was seventy-five thousand pounds ($150,000). Cinerama supplied all of the technical equipment, almost down to the last nut and bolt. They retained ownership of the gear, and leased it to the cinema proprietor. The films themselves were rented in the conventional way, with a guarantee against a percentage of the takings. The distributor was the Stanley-Warner Corporation. Melbourne’s equipment came from Loew’s Teck in Buffalo New York, which had closed in February 1958. Its screen had been 78 feet wide and 28 feet high (24m x 8.5m). It had to be cut down to 64 feet by 23 feet (19,5 x 7m) to fit into the Plaza. Unusually, this screen had a ‘solid’ centre panel instead of being completely vertical louvres, as was the normal Cinerama practice. The usual curvature of a Cinerama screen was 146 degrees, but due to a lack of useable stage depth, the Plaza could only accommodate a curvature of 120 degrees, or a depth of 12 feet (3.7m). As it happened, the screen fitted neatly between the organ chambers on either side of the stage, just in front of the old proscenium. A new stage apron was built, curving out into the auditorium. The stage was relatively low and the top and bottom screen masking was narrow in order to expose the maximum screen area. There was no adjustable side masking. The smallish Wurlitzer organ, with its two manuals and 12 ranks, remained functional, though the console was moved backstage. It was never played publicly, but the Regent’s organist used it as a practice instrument. The Plaza had always been fitted with ‘lounge-style’ seats rather than ‘tip-up’ chairs, though the original embossed-leather seats had been replaced after the war. The ‘lounge’ seats were retained, but seating capacity was reduced from 1235 to 865. |

|

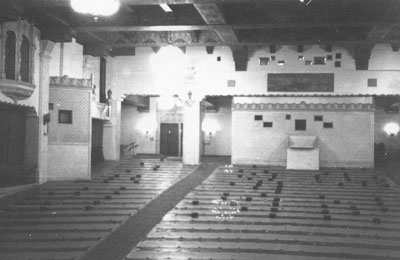

Inside the upstairs projection room: the large sound reproducer, its pre-amplifier rack and the electrical film lifting machine on the right. The back of the prologue projector is just visible (left). Image courtesy of Ross Thorne. Inside the upstairs projection room: the large sound reproducer, its pre-amplifier rack and the electrical film lifting machine on the right. The back of the prologue projector is just visible (left). Image courtesy of Ross Thorne. It was Cinerama’s policy in all its theatres to have a rich red curtain following the curve of the screen. In the Plaza, the curtain curved outwards slightly at the sides to cover the organ chambers. Red curtains were also used to hide the old promenade area on either side of the auditorium and dampen the acoustics. The two side projection rooms protruded slightly from the promenade area near the rear of the theatre. The centre projection room sat under the original bio-box. Their outside walls were tastefully decorated with a criss-cross moulding pattern that sat well with the Plaza’s stuccoed plaster. The stage curtain was illuminated by ten ‘baby’ spotlights mounted on the top of both the side projection rooms. Cinerama had up to three installation teams working around the world at any one time. While the Plaza was being equipped there was another crew working in Spain. Melbourne’s installation was directed by an American, Frank Richmond. Cinerama appointed Ron Chambers as their technical representative in Australia. He had worked on Cinerama in London. He was involved in the Melbourne installation and after Cinerama was up and running, he divided his time between the Sydney and Melbourne theatres. During the re-construction period, Hoyts engineer, Ken Neck began assembling a projection crew. Victorian Government health regulations of the time required that each projector be attended by a licensed operator. Cinerama also had its requirements. There needed to be a program-control engineer and an additional projectionist to supervise the sound reproducer (which was in the Plaza’s original upstairs projection room), show the prologue film and operate the lights. This meant that every show required a technical crew of five. Various experienced projectionists were invited to join the team. They were required to commit themselves to a year’s involvement. If they then wished to move on, they could do so as vacancies arose in other theatres. Ted Sharry, who had been working at the Athenaeum, became the head picture control engineer, with Bill Watson as his deputy. Other projectionists were Don Albon, Alan Wynne, Noel Brabet, who had already been working at the Plaza, Ozzie Taylor, David Downing and Bill Cleaves. They were given a week or two of training before the public opening. |

|

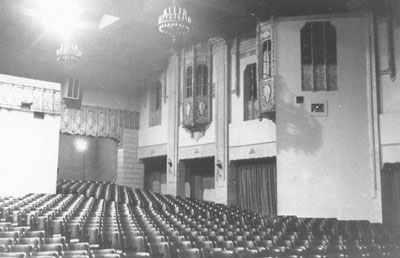

The

Able projection room and curtained-off "promenade" area. Photo credit, Wayne

Brown The

Able projection room and curtained-off "promenade" area. Photo credit, Wayne

BrownAbout a month before the opening, a discreet mention of Cinerama appeared in the Hoyts City Theatres advertisements. ‘Cinerama Is Coming,’ it said, in the space reserved for the Plaza. There was little other publicity in the press. Normally, in the U.S. Cinerama stuck to a tried and true pre-opening strategy, refined over the preceding five years. Before the opening date, its representatives would roll into town, creating relationships with civic and commercial movers and shakers and liaising with community groups. Publicity stunts would be set up and a big premiere involving a local charity organized. This was pretty much what happened in Sydney, but for Melbourne the publicity was low-key, especially when compared with that for The Ten Commandments, which had commenced at the nearby Barclay on 11 December. Cineramas’s publicity people did not stay on in Australia after the Sydney opening. Consequently, there were only a few modestly-sized block advertisements for "This Is Cinerama" in the Melbourne press prior to the opening date, apart from the information, from 16 December that bookings were now open for a season starting on 26 December. Cinerama opened for business at the matinee on Boxing Day 1958. There was to be a restricted performance policy with only three shows a day. This followed the pattern set by Mike Todd for "Around The World In 80 Days", where the idea was to present ‘performances’ of a ‘show’ rather than sessions of a movie. All tickets were ‘on block’ for reserved seating. Bookings could be made weeks ahead, as for a stage show. There were only three sessions a day, six days a week. Seat prices were also up market. They ranged from eight shillings (80c) at an afternoon session in the cheapest seats to sixteen and six ($1.65) for a Saturday night in the most expensive seats. Though there was no gala premiere for "This Is Cinerama", there was a special midnight show on New Year’s Eve. Roberts Dunstan, in reviewing " This Is Cinerama" on 27 December wrote, ‘The effect is overwhelming…I’m still dazed…In terms of size and noise, Cinerama outdoes other wide screen processes.’ He added, however, that the film was ‘no more than a travelogue.’ The public was not put off. They took to Cinerama with enthusiasm and full house followed full house. |

|

The projection equipment all came from the Teck theatre in Buffalo after storage at Cinerama’s technical headquarters on Long Island New York. It consisted of Century (Centrex) 35mm heads modified for a six sprocket-hole picture pull-down, driven by special variable speed gearboxes regulated by the picture control engineer. There was a separate take-up spool motor. The heads had water-cooled gates. The arc-lamps were large ‘Strong’ units, using 10mm ‘black’ carbons and 8mm copper-coated negatives, running at about 100 amps. The positive carbons were fed and rotated during operation by a water-cooled jaw mechanism close to the positive crater. There was adequate trim for the lamps to run for the hour or so that made up each half of the Cinerama program. The lamps had metal mirrors. In the nose of the lamphouse a tilting grid could alter the amount of light falling on the back of the projector gate, in order to even up the brightness of each of the three screen panels. By all accounts, the lamps ran very reliably. The spools were over 30 inches in diameter (70cm) and held eight thousand feet of film (2400m) or more. Because of their weight, they fitted on to half-inch spindles (as with 70mm spools.) Each projector had a motorized film-lifting device that raised the spool from floor level up to the feed spindle. The projection equipment all came from the Teck theatre in Buffalo after storage at Cinerama’s technical headquarters on Long Island New York. It consisted of Century (Centrex) 35mm heads modified for a six sprocket-hole picture pull-down, driven by special variable speed gearboxes regulated by the picture control engineer. There was a separate take-up spool motor. The heads had water-cooled gates. The arc-lamps were large ‘Strong’ units, using 10mm ‘black’ carbons and 8mm copper-coated negatives, running at about 100 amps. The positive carbons were fed and rotated during operation by a water-cooled jaw mechanism close to the positive crater. There was adequate trim for the lamps to run for the hour or so that made up each half of the Cinerama program. The lamps had metal mirrors. In the nose of the lamphouse a tilting grid could alter the amount of light falling on the back of the projector gate, in order to even up the brightness of each of the three screen panels. By all accounts, the lamps ran very reliably. The spools were over 30 inches in diameter (70cm) and held eight thousand feet of film (2400m) or more. Because of their weight, they fitted on to half-inch spindles (as with 70mm spools.) Each projector had a motorized film-lifting device that raised the spool from floor level up to the feed spindle.The sound track was on a separate 35mm film, fully coated with iron oxide, to take the six or seven track magnetic stereophonic sound. (The number of tracks varied from production to production.) This was run on a seven- foot tall (2.1m )oversized tape-recorder which was located in the Plaza’s original upstairs projection room. Next to it was a pre-amplifier rack of similar size. This projection room also contained a conventional 35mm Centrex projector with a ‘Westrex 14’ lamphouse on which the prologue films were shown. This projector had its own sound system. Also in this projection room were the theatre lighting dimmers and a bi-unal slide projector. Initially, screen slide advertising was against Cinerama policy, but later on slides were shown, only occupying the screen’s centre panel. There was no ‘non-synch’ music. |

|

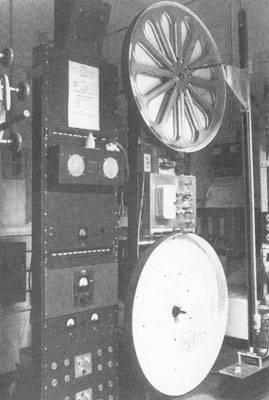

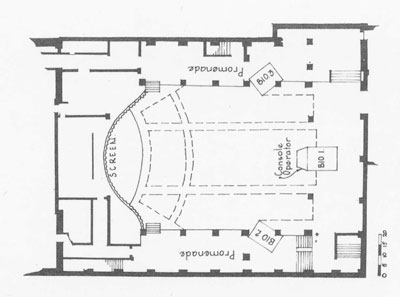

The

Plaza floor plan after the Cinerama renovations. Plan courtesy of Ross

Thorne. The

Plaza floor plan after the Cinerama renovations. Plan courtesy of Ross

Thorne.The power amplifiers were provided for Cinerama by Altec-Lansing, as were the speakers. The amplifiers each had a huge output of 75 watts RMS. (A conventional theatre amplifier of the time had an output of 30 watts. The Regent’s sound system, by contrast had an output of 60 watts per channel.) It was the practice in some Cinerama theatres to have the amplifiers on stage, but in Melbourne they were distributed around the three ground floor projection rooms. In accordance with Cinerama’s high presentation standards, every morning, before screenings commenced, an eight kilocycle sound test loop was run to check the efficiency of the sound system. The three ground floor projection rooms did not have monitor speakers, so the projectionists were not able to listen to the movie sound track, nor could any one projectionist get a view of the whole screen. Cinerama was very fussy about the cleanliness of the film. They had pioneered the use of splicing tape for joining film, and then as now, tape splices collected dirt. Multiple copies of each production were held at the theatre so that one print could be cleaned while the other was in use. Cinerama had its unique cleaning material, a mixture of Shellite and Brasso, which effectively removed signs of wear. There was also a special film-waxing machine. The cleaning was done in a special room built in the promenade area, to the side of the auditorium. If there was a spare projectionist on a shift, as sometimes happened, he was set to cleaning film. It was not a popular job. |

|

The

"Baker" projection room of the SYDNEY Plaza, after extensions to accommodate

the 70mm projectors. (Note the "Cinerama" shield on the front of the console

booth). Photo credit, Wayne Brown. The

"Baker" projection room of the SYDNEY Plaza, after extensions to accommodate

the 70mm projectors. (Note the "Cinerama" shield on the front of the console

booth). Photo credit, Wayne Brown.Each projection room was equipped with an electric re-winder. While re-winding the film, the projectionist wore a silk glove on his left hand, to feel the sprocket holes for damage. As the glove was silk, there was no static electrical charge built up in the film. (Such electrical charges attract dust.) A further measure to keep dust of the film was to keep the projection room closed at all times. Although the projection rooms were mechanically ventilated, they could become very stuffy. Even so, the door had to be kept closed, by Cinerama’s order. The console operator, sometimes known as the picture control engineer, worked from a little booth in front of the centre projection room. His job required high concentration and constant vigilance. He was in touch with each of the four projection rooms by intercom. He started the equipment by remote control, was able to monitor the speed of each projector and adjust it if necessary to correct the synchronisation of the projectors, and keep an eye on general picture and sound quality. He was also responsible for the most important and spectacular moment in the show, the changeover from the conventional 35mm prologue to Cinerama. His booth was partly screened off from the audience, but he still had to make his way through the seats to get to and from it, trying to avoid being accosted by small boys (such as myself), ready to plague him with obscure technical questions. Such questions were always answered graciously, however. Cinerama ran a tight ship. Such a technically complicated system required discipline and team work and there was no room for individualism in the technical crew. The projectionists were all highly experienced and used to running their own projection rooms, so some found working for Cinerama irksome. The compensation lay in the fact that city projection jobs were prized. They paid a little better than the suburban rate, and there was not the necessity for constant night work. Even so, after a year or two, some of the projectionists chose to move on and were replaced by fresh faces. In Britain by contrast, Cinerama projectionists were very well paid and the job was highly sought after. The same applied in Europe and the U.S.A. Many regarded it as the ultimate projection job. For some years, things ticked over in a routine way, with each of the six Cinerama ‘travelogues’ enjoying long runs. In early 1960, however, Nicholas Reisini of Robin International, took over all of Stanley-Warner’s interests. Reisini entered into an agreement with M.G.M. to co-produce two narrative-style Cinerama films, "How the West Was Won" and "The Wonderful World Of The Brothers Grimm". Meanwhile he also took over the Cinemiracle company, developers of a process very similar to Cinerama, and with it, their one and only production, "Windjammer". This film was then presented in Cinerama theatres. It was effectively the end of the travelogue format. "Windjammer" finished its season at the Plaza on 31 December 1962. "How The West Was Won" started on New Years Day, with some fanfare, courtesy of M.G.M., and a visit to Melbourne by one of the film’s stars, Henry Fonda. It was a huge success world-wide and ran in Melbourne for almost two years. It was followed by "The Wonderful World Of The Brothers Grimm". This had not met with the same success as "How The West Was Won" overseas, but still had a respectable six month run in Melbourne and did very good school holiday trade. M.G.M. decided not to go any further with Cinerama. They had just had a bad case of production horrors with the Brando version of "Mutiny On The Bounty" and were still recovering. Cinerama held hopes of being used for "Cleopatra" and "The Greatest Story Ever Told", but it was not to happen. High production and presentation costs had caught up with the medium just at the time block-buster films were no longer bringing in the money they once did. The era of three-strip production for Cinerama was over. In Melbourne, the Plaza’s projection staff were advised about one year in advance that no more films would be made in the medium. Future Cinerama films would be photographed and projected in the 70mm format, commencing with "It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World". There were a couple of three-strip films that never reached Melbourne in that form. They were "Holiday In Spain" and "Cinerama’s Russian Adventure". Neither did that well anywhere. ("[Cinerama´s] Russian Adventure" had a brief run in 70mm at the Chelsea in 1966.) "The Wonderful World Of The Brothers Grimm" finished its run on 2 June 1965. The next day, " It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World" opened in ‘single lens’ Cinerama, with a grand premiere at 7.30 pm. There was a parade of glamorous models with Mad, Mad World hairstyles while the Red Onions Jazz Band played. Then on Friday 4 June it was back to three sessions a day. The Plaza never closed for its conversion to single-lens Cinerama, though there were no day sessions on the day of the premiere. This was quite an achievement, as the centre projection room had to be enlarged and a pair of 70mm Cinemeccanica Victoria 8 projectors with Ashcraft lamphouses installed. This was done in special pre-show shifts. Some seats had to be sacrificed. The capacity was reduced from 865 seats to approximately 811. Cinerama supplied custom-built projection lenses capable of achieving an evenly sharp focus over the deeply curved screen. All of the three-strip equipment stayed in place, though presumably Hoyts were no longer paying rent on it. There was little point in removing it. Cinerama now had a great surplus of plant and to send it back to the U.S. would be needless expense. The three-strip prints also stayed in Australia. Though it never happened in Melbourne, in some overseas venues, there was the occasional revival of a three-strip show. Now the Plaza projection crew was reduced to the conventional system of staffing, with one projectionist and an assistant on each shift. Places were found in other theatres for the superfluous staff. Ted Sharry stayed on as ‘chief’, with Don Albon on the opposite shift. Though single lens Cinerama was not as visually effective as the three-strip system, audiences took to it. " It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World" ran for over a year and started the wave of big-screen slap-stick comedies of the sixties. None of the later 70mm Cinerama films did quite as well. The average run was three to four months. "Battle Of The Bulge", "Grand Prix" and "Khartoum" were some of the shows. "2001: A Space Odyssey" ended the continuous, ten year, Cinerama run. Many people found " 2001: A Space Odyssey" incomprehensible, and it ran for less than three months. It probably made the best use of the process of any of the Cinerama films, however, and is now considered a classic. The Plaza found itself temporarily without a Cinerama feature when " 2001: A Space Odyssey" finished its run at the end of May 1968. Hoyts at the time were short of 70mm outlets. Their Cinema Centre was not to open until June 1969 and the Esquire and Paris, the two other 70mm houses, were tied up with long runs. "Hawaii" had to run at the Athenaeum in 35mm and "The Bible", in 70mm was give to the Capitol, which had long ceased to be a Hoyts theatre. "Around The World In 80 Days" was due for a tenth anniversary re-release and for the first time in Melbourne in 70mm Todd-AO. (The 1958 season at the Esquire had been in 35mm Cinestage, a non-standard anamorphic process.) It was now to go into the Plaza. |

|

The

"Charlie" projection room at the Sydney Plaza Theatre. The Sydney conversion

was less discreet architecturally. Photo Credit, Wayne Brown. The

"Charlie" projection room at the Sydney Plaza Theatre. The Sydney conversion

was less discreet architecturally. Photo Credit, Wayne Brown.For legal reasons, Cinerama’s equipment could not be used for presenting non-Cinerama shows. This meant that in order to present " Around The World In 80 Days" the Cinerama vertical louvred screen would have to be replaced. A ‘single-sheet’ conventional screen following the same curve was installed and the Altec-Lansing speakers were replaced with second-hand Westrex A4 units. There was no loss of sound quality. A conventional Westrex six-track stereo sound system was also in place, complete with an ‘integrator’ for split left, rear and right sound on the surround track. The special Cinerama lenses were also replaced and the screen slightly reduced in width. There was a small problem of cross reflection of light from one side of the screen to the other. The film ran for three months. Further technical decline was to follow. The next film was not even 70mm. It was "The Fox", a tasteful but avant-garde tale of suppressed lesbian love. Art films were becoming mainstream cinema fare and it ran for a month. It looked satisfactory on the masked down screen. The Christmas attraction, "The Charge Of The Light Brigade" was at least Cinemascope and it did good business. After that, there was a return to 70mm Cinerama with "Custer Of The West" and "Ice Station Zebra", which finished at the end of June 1969 when Hoyts Cinema Centre opened. The Cinema Centre now got the best of Hoyts product and the old theatres showed the lesser stuff. The Paris began to run continuous sessions of difficult-to-program films such as "The Staircase" and the Esquire drifted to action shows. The Plaza ran a bit of everything. There was Peter Sellars’s "The Party", a 70mm revival of "West Side Story", Omar Sharif as "Che" (Guevara) and Anthony Quinn dancing across the screen yet again as "Zorba The Greek". None of these seasons lasted too long. The last gasp of Cinerama was "Krakatoa East Of Java". It was a school holiday attraction and that was all that saved it. The people who realized that Krakatoa is west of Java avoided it. It was a less than mediocre film and a sad end to Cinerama in Melbourne. The Plaza did end in a blaze of glory, however. Hoyts had booked a hit into the place, "Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid". It ran from 26 February 1970 and closed the Plaza on 4 November 1970. While " Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid" continued at the Plaza, above it the Regent, once the prize of the Hoyts chain, closed in June 1970. Hoyts had investigated the possibility of ‘twinning’ the Regent in the same way Greater Union had twinned the State, but decided that it was more practical to build the Cinema Centre, three modern auditoriums with a common foyer, restaurant and office tower above. Once this opened the Regent’s fate was sealed. It was a strange night-time sight, the once inviting entrance now dark while the Plaza was lights and bustle. If the Regent had to go, so eventually would its small sister. The Plaza might have been expected to close on the same day as the Regent, but it was doing too well with Butch Cassidy. Meanwhile, Hoyts was short of one city outlet as the Athenaeum had been sub-let to a live theatre company, Philip productions, earlier in the year. (When this venture failed the Athenaeum reverted to films.) When the Plaza closed in November, Ted Sharry the Plaza’s surviving projectionist, then crossed back over Collins Street to resume operating at the theatre he had left 12 years earlier in order to work at Cinerama. The fittings from the Plaza and Regent were sold at auction late in 1970. The Plaza’s organ had been removed in 1968 and sold to the Theatre Organ Society. It was installed in the auditorium of a private school in Adelaide, where it remains today. The Cinerama equipment and prints were sent to a Hoyts warehouse in Sydney, where they were eventually joined by the equipment from the Sydney Plaza which closed in 1977. The equipment then went in various directions. Four of the arc-lamps went to Victorian Drive-In theatres. Two of the projector heads were restored to conventional 35mm use and went to a Sydney outer suburban theatre. Some of the equipment ended up in private hands. It was frequent practice throughout the world for Cinerama equipment to be abandoned where it stood. Even today, 35 years after the last official screenings, equipment and prints pop up from time to time, and in unlikely places. Cinerama continued for a few years as a film distributor. The last 70mm show it released was "Song of Norway". It ran at the Cinema Centre for a year. The Cinema Centre had been equipped with deeply curved screens and genuine Cinerama projection lenses, but there was never another Cinerama presentation. The Regent and Plaza were purchased by the Melbourne City Council and lay derelict for 25 years. The story of their rescue and restoration is well told by Frank van Straten in The Regent Theatre –Melbourne’s Palace of Dreams The Sydney Plaza is also still standing, but as a hamburger restaurant. |

|

Acknowledgments |

|

This

article originally appeared in CINEMARECORD, published This

article originally appeared in CINEMARECORD, published quarterly. It is the magazine of the Melbourne-based Cinema and Theatre Historical Society (Victoria) The International Cinerama Society, David Coles, Ted Sharry and the Melbourne Cinerama projectionists, Gil Whelan, David Kilderry, Ken Mogg and Brian Beatty and Ross Thorne. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |