Fabulous Technicolor!

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Les Paul Robley, Film & Video Critic, Los Angeles, USA and proofed by Tom Kuhn and Chris Regan of Deluxe Labs | Date: 09.02.2010 |

Well, I wonder… Well, I wonder…Do you see me when I pass? I have died. Please keep me in mind… --Morrissey As a film collector for many years, it’s sad to think that motion picture film will someday be a thing of the past. With the price of 2K home digital projectors plummeting much like the housing market in California, this may happen sooner than you think. Analysts say that by the year 2012, 24,000 U.S. movie screens will be digital (not film!) at a cost of approximately $80,000 per screen. When I see the various websites offering film prints for sale, I smile when I see ads listing recent movies with the words “Beautiful LPP low fade” to describe their condition to potential buyers. Whether you know it or not, the code LPP printed on the edges of 35mm and 16mm positive print film disappeared around 1993, that is, according to Deluxe Labs, Protek Film Vaults and various prints inspected from that time. Seeing a print of "Norbit" listed with the letters LPP isn’t going to make me want to rush out and buy it any faster than if the letters weren’t there, since everything is low fade nowadays. So, I thought it might be interesting to do some research on the various color print stocks from 1900s to the present, in order to see just how the symbol LPP came about. The seventies proved a sad decade for film collecting. Technicolor shut down its imbibition (IB) dye transfer Cahuenga facility in 1975. Its new lab next to Universal Studios became an Eastman-only processor. Technicians who worked at the Hollywood lab claim that the last new American film released before Technicolor ceased printing dye transfer was Disney’s uninspired adaptation of Jules Verne’s "Island At the Top of the World" (1973). Other sources say it was "The Godfather, Part II" (1974). (I have an I.B. Technicolor 35mm reissue print of Disney’s "Swiss Family Robinson" with edge code symbols of 1974 visible on some reels.) So, who knows for certain the last film released in IB in America? In 1977, Dario Argento used the last dye-transfer printer in Rome for "Suspiria" (1978). Put simply, gone were the days when one could purchase a nice No-Fade 35mm I.B. Tech print of a movie from the seventies, like "Jaws" (1975) or "Star Wars" (1977), unless you were lucky enough to obtain it from England where the IB process was still employed. Technicolor was the second major color film process for motion pictures (following England’s Natural Colour Kinematograph Company), and the most mass-produced color motion picture process in Hollywood from 1922-1952. Not only did it afford a richer, almost 3-dimensional look to film, but, from an archivist’s point of view, it possessed one very cool quality: It was virtually fade proof! Since 1982, Eastman color film stocks like LPP have also been “low fade,” but Technicolor dye-transfer prints have been “no fade” since the 1920s. Since a Tech print employed stable Azo dyes (dyes which are also used in current DVD technology), it could retain its original colors for decades. Even when stored under improper conditions, the colors in a Technicolor print survived longer than early Eastman color prints that might maintain only the magenta record after a mere ten years. Almost a novelty when introduced during the mid-teens, nothing with regards to dye stability seems to have outlasted the old IB process of 3-strip dye-transfer printing. The Father of Technicolor, Dr. Herbert Kalmus, developed the technique with Daniel F. Comstock and W. Burton Wescott in 1915 inside a railway car equipped with chemical laboratory, darkroom and fireproof safes. Preferring the Old Dutch Masters to film and shunning any kind of screen credit, his first-wife Natalie received the title of color consultant (some say unworthily) on virtually every studio film produced with the process until 1949, the expiration date of their patent. Actually, the basic idea evolved as far back as 1855 when physicist James Maxwell employed Newtonian science to add color to a bowl of fruit by superimposing three pictures through red, green and blue filters. This came about only 30 years after what is generally regarded as the first permanent photograph taken by Frenchman Joseph Niepce using bitumen (or asphalt from the Dead Sea) as the light-sensitive material. All bitumen is light-sensitive to some extent, but the kind found in Judea has a particularly strong reaction to light. Niepce coated a metal plate with it, and wherever the light exposed, the bitumen hardened. The unhardened parts that were unexposed could then be washed away using lavender oil. The negative image remained, which could later produce positive prints on paper. Niepce’s first photograph—the courtyard of his Provencal farmhouse—took eight hours to produce, giving an interesting effect of the sun illuminating both sides of the courtyard at the same time. In 1839, Louis Daguerre founded the principle of the “latent image”—the idea that some chemicals react to light quickly, but do not reveal an image until they are developed by further chemical treatment. He used a silver iodide image, “fixing” it with common table salt. In the same year that Daguerre announced his discovery, Fox Talbot invented the first paper printing process. But to give color credit where credit is due, dye-transfer printing has been dated back to 1875 when E. Edwards invented the Hydrotype or Imbibition printing process. Before Kalmus’ system, early forms of creating color in black-and-white silent images applied the tedious method of hand-painting each frame of film or tinting an entire scene with filters over the projector. Many of George Melies’ early silent trick films and D.W. Griffith’s famous "Birth of a Nation" (1915) employed this method. Other techniques involved “toning” or bathing an entire section of film in a color solution, such as early Kodascope prints of "The Lost World" (1925). The second means of applying color to film involved a primitive two-color “additive” system, the first practical and successful being Kinemacolor, patented in Great Britain in 1906 by George Albert Smith and Charles Urban. In 1911, they produced the first major color film, "The Durbar at Delhi", using black-and-white film combined with red-orange and blue-green filters. The film was projected at double speed (32 frames-per-second) so that the filtered images alternated for each frame. A rotating color wheel synchronized with the projector motor, and the principle of persistence-of-vision (the phenomenon that enables us to see moving pictures), brought the colored images together. The effect was not all that bad, but similar problems which plagued early 3-D systems—such as eye strain, bleeding of colors and added wear on the film—soon doomed this process to eventual abandonment. In 1915, Kalmus and Comstock experimented with a two-color additive process utilizing a beam splitter prism behind the camera lens and exposing two adjacent frames on a single strip of black-and-white negative simultaneously, each equipped with its own red and green filter. Again, the film had to be photographed and projected at twice the normal speed. According to the documentary, "Glorious Technicolor", only a single frame of film exists of the very first non-tinted color motion picture, "The Gulf Between", financed by Technicolor and starring Grace Darmond and Niles Welch. Exhibition of the image required a special projector with double apertures containing the red and green filters, two lenses and an adjustable prism to align the two images on screen. Kalmus wrote: “I decided that such special attachments on the projector needed an operator who was a cross between a college professor and an acrobat.” Color cinematography was still considered a novelty when inferior 2-strip “subtractive” processes were introduced in the early 1920s with films like "Toll of the Sea" (1922), color sequences from Cecil B. De Mille’s silent "The Ten Commandments" (1923), "Ben-Hur" (1925), the Masque of the Red Death scene from "Phantom of the Opera" (1925) and the entire "The Black Pirate" (1926) starring Douglas Fairbanks. The single black-and-white negative was exposed in much the same way as Kalmus’ additive process. The difference resulted in the making of the print. The red and green sensitive film strips were physically cemented together base to base, and although thinner than regular film, the combined thicker print caused cupping and scratching when projected. Also, as the two welded prints did not share the same frame, sharp focusing became an issue. During the transition to talkies, many studios employed variations of a 2-strip Technicolor technique created by Max Handschiegl in 1916 in order to enhance their song and dance musical numbers and eliminate the need for double-cementing prints. This employed a process similar to lithography referred to as dye-imbibition and was based on the early plate or matrix method invented by Niepce way back in 1826. The red-and-green-filtered negatives were printed onto separate strips of blank film coated with gelatin which hardened in proportion to the amount of light that struck it. The softer gel was washed off leaving a relief image of the hardened gelatin. The matrices were soaked in dyes of complementary (opposite) colors—the strip containing the red record was dyed green and vice versa—and these matrices were then “dye-transferred” to a third blank film print coated with a substance to absorb the dyes. As they did with sound, Warner Brothers studios led the way by producing the now-classic 2-strip Technicolor prints of "Manhattan Parade" (1932), "Doctor X" (1932) and "The Mystery of the Wax Museum" (1933), the latter two with Fay Wray. They had originally planned to produce six features with the new process, but the extra expense and a Depression-jaded public signalled an end to the first color boom. Kalmus always dreamed of developing a full three-color process, and by 1929, Technicolor was well on the way to achieving it. He envisioned a special beam splitter camera equipped with a 45-degree gold-flecked mirror (between prisms) whereby light entered the lens through a single entrance pupil and was absorbed by negatives sensitive to each of the three primary colors: green, red and blue. An extremely heavy camera ran three black-and-white films simultaneously—one sensitive to green light, one to red, and another to blue. One-third of the light transmitted through the beam splitter and green filter onto a panchromatic film stock. The other two-thirds reflected sideways through a magenta filter onto blue-sensitive orthochromatic film sandwiched or “bipacked” with a red-sensitive strip of panchromatic stock. After processing, each negative, in turn, was optically printed onto a matrix-type film which resulted in three positive relief’s containing varying components of a gelatin image—the more the exposure, the greater the residual gelatin. To obtain a 3-color print, the matrix resulting from the blue-sensitive negative was passed through a solution of yellow (blue-light absorbing) dye. The higher the amount of gelatin, the more the dye was absorbed. Next, this matrix was placed into contact with a blank black-and-white print film and the yellow dye was transferred. All three complementary yellow (blue-light absorbing), magenta (green-absorbing) and cyan (red-absorbing) dyes were transferred onto this single film emulsion, reproducing the full spectrum of color. (This dye-transfer technique was similar to Kodak’s still photographic method for making prints from a Kodachrome slide original.) Kalmus convinced Walt Disney to film one of his popular Silly Symphony cartoons in this 3-strip process and a true three-color system debuted in 1932 with “Flowers and Trees”. Cinematographers were now able to obtain true color, control contrast and be more expressive with their lighting. Plus, the dye-transfer process afforded tremendous color stability resulting in color prints that would virtually last one’s lifetime. According to October 1934 Fortune Magazine, “Marion C. Cooper, producer for RKO Radio Pictures and co-director of "King Kong" (1933), saw one of the Silly Symphonies and said he never wanted to make a black-and-white picture again.” He, along with John Hay Whitney, financed the first 3-strip, live-action Technicolor short, "La Cucaracha" (1934) for $65,000 (roughly four times what an equivalent twenty minute two-reeler would cost in black-and-white). It’s interesting to note that Cooper went on to produce "She" (1935) and "Mighty Joe Young" (1949) in black-and-white despite his preference for color. According to stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen, this was done for budgetary reasons. Harryhausen has since supervised colorized versions of the films on DVD for KINO International. |

More

in 70mm reading: A History of Widescreen and Wide-Film Projection Processes Internet link: Les Paul Robley 40 Sunset Circle Westminster CA 92683-8000 USA IBsonly@aol.com & mymo_co@yahoo.com |

Three other live-action films were released earlier, beating Cooper to

the punch. MGM’s "The Cat and the Fiddle" and the WB’s shorts "Service With

a Smile" and "Good Morning, Eve!" apparently came out before "La Cucaracha"

that same year, each containing 3-strip Technicolor sequences. But in

1935, Pioneer Pictures and RKO produced "Becky Sharp", which became the

first full-length Technicolor feature. Designed by Robert Edmond Jones

(and photographed by Ray Rennahan), this ponderous adaptation of

Thackeray’s "Vanity Fair" is considered historically significant if only

for its beautiful color and the fact Rouben Mamoulian directed it. A

year later, "The Trail of the Lonesome Pine" became the first film to have

outdoor scenes shot in 3-strip Technicolor. This proved significant

because the extremely slow film and light-loss through the beam splitter

required very intense lighting. Temperatures on sets often exceeded

38-degrees Celsius (100-degrees Fahrenheit) and some actors complained

of eye fatigue due to the high levels of illumination. On "The Wizard of

Oz" set, for example, some heavily costumed characters purportedly

fainted due to the extremely high heat levels and loss of body

perspiration. Buddy Ebsen, the original Tin Man, apparently became sick

and was hospitalized due to the bright aluminum dust sprayed on his

costume, thus losing the part to Jack Haley. "70mm

reissue of "Gone With The Wind" 3-sheet poster. "70mm

reissue of "Gone With The Wind" 3-sheet poster.Technicolor reached its zenith renting cameras to the studios from the late ‘30s through the ‘50s with one million feet of film being processed per day. It did more to enhance American and British costume dramas and musicals, such as WB’s "The Adventures of Robin Hood" (1938), MGM’s "Gone With the Wind" and "The Wizard of Oz" (1939), as well as Powell & Pressburger’s sumptuously photographed "Black Narcissus" (1946) and "The Red Shoes" (1948). It’s interesting to point out that critics noticed a difference between a Technicolor film made in England—which produced a softer, more diffuse color—than the normal heavily-saturated Hollywood look. Some say this was due to the inherent overcast, foggy look of the British Isles. Even underdog Universal, a studio boasting no stable of real stars, used the process to make their own: Maria Montez—the Queen of Technicolor—as showcased in the film, "Cobra Woman" (1944). Disney’s animated features, like "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs", proved extremely adaptable to the 3-strip process, since their massive multi-plane camera could be loaded with a single black-and-white negative film. Each animation cel could then be photographed three times behind green, red and blue filters on subsequent frames. Normally the soundtrack image would be pre-printed onto silver-based black-and-white stock, which would then be brought into contact with each of the three dye-soaked strips. That is why the process is referred to as “dye transfer.” The dyes are soaked into the emulsion which makes them very stable and less likely to change over time. One can usually recognize an IB print by its black-and-white soundtrack. Registration of the three elements was absolutely critical, otherwise color fringing could occur. Early on, the unexposed film was “pre-flashed” or pre-exposed with a 50-percent neutral density positive image to conceal this fringing and print black lines between frames. However, colors became muted as a result. Later, Technicolor discontinued this technique in order to streamline the process. That is why film collectors prefer a clear-edge IB print (as opposed to one with dark edges) because the color is more vibrant in the former. In 1954, the era of glorious Technicolor came to an end with "Foxfire", the last American film to employ the bulky 3-strip camera. George Eastman, who originally declined the opportunity to finance Kalmus, introduced a “monopack” single strip negative during the late ‘40s known as Eastman color, which made every camera capable of filming color. In 1948, Kodak announced a 35mm tri-acetate safety base film to replace the flammable cellulose nitrate stock. Complete conversion from nitrate to safety took about four years, and Eastman followed this in 1950 with 5247 and 5381, the first Kodak incorporated color-coupler camera negative and print films in 35mm. These stocks were replaced two years later by 5248 (color negative) and 5382 (color print film), both with faster speeds and image structure improvements. |

|

|

Once perfected, the single film system became the industry standard, so

smaller, more portable cameras could be used and manufactured by anyone.

Technicolor lost their camera rental monopoly to Kodak and was forced to

adapt its dye-transfer process using three-color separations to make

prints from the new Eastman negative. It’s interesting to note that the

dye transfer release prints never faded, whereas the negative from which

they were derived often lost the cyan record in five years. Many of Technicolor’s blue 3-strip cameras were converted to large format 8-perf VistaVision, incorporating a peculiar half-twist in the film-threading pattern in order to expose the negative 8-perforations horizontally (rather than the standard 4-perf vertical method). A 1.5 reflective lens “squeeze” was added in front of the spherical lens to achieve a 2.35:1 CinemaScope aspect ratio for post-1953 movies. Since the lens attachment used mirrors to squeeze the image meant there was no light-loss as found in typical anamorphic Cinemascope lenses. They renamed the process, Technirama and one G-6 labeled camera was used on "Spartacus" (1960), later owned by Introvision for shooting VistaVision background plates. (The larger, double-sized negative afforded a copy ratio of 2-to-1, so the front-projected backgrounds exhibited less grain when re-photographed onto standard 35mm 4-perf film.) Kalmus sold his interests in 1960 to ballpoint pen magnate Pat Frawley, who went on to diversify the company. But Technicolor always needed to maintain at least two working 3-strip cameras on the lot in order to maintain rights to their patent. The father of Technicolor died on July 11, 1963, just when 007 fever was at a high producing Tech prints of "Dr. No". In 1974, new management at Technicolor terminated the dye-transfer technique in favor of the more economic single-film processing. Three of the last dye-transfer prints to emerge from America were the film adaptations of the Broadway musicals, "Fiddler on the Roof" and "Cabaret", and Mario Puzo’s "The Godfather". These and other films of the early '70s practically signaled a death-knell to the IB process by virtue of the fact they hardly even utilized the color that was at their disposal. Musicals have typically flaunted Technicolor at its best: Eye candy that accentuates all the colorful costumes and fantastic staging as in MGM's luscious Esther Williams underwater vehicles and Fox's Betty Grable pictures (the latter with her “peachy complexion and shapely legs glowing in Technicolor” wrote one smitten reviewer). But in "Fiddler"’s case, the color was almost downplayed to a muted sepia effect. It was even shot through a gauze filter, as if to emphasize the impoverished Ukrainian village of Anatevka (actually filmed in Gorsky Kotar, Croatia). Although director Norman Jewison has been criticized for his literal-minded translation of the play to the big screen, the film surprisingly won an Academy Award for its cinematography by Oswald Morris. |

|

So what happened to dye-transfer? |

|

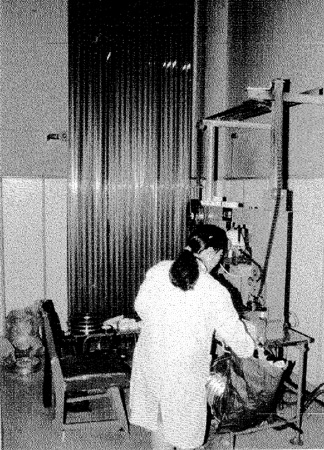

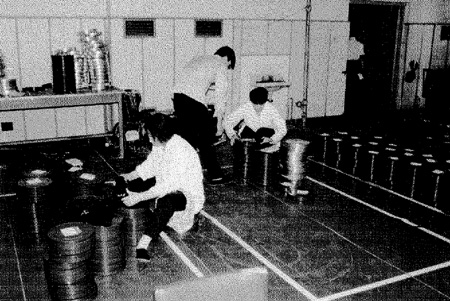

3-strip

dye transfer lab in Beijing, China using Technicolor equipment from England

before it closed in 1993. Photo taken by Les Paul Robley in August of '93. 3-strip

dye transfer lab in Beijing, China using Technicolor equipment from England

before it closed in 1993. Photo taken by Les Paul Robley in August of '93.The popular story among film collectors is that Technicolor Labs phased out IB printing in Hollywood because the independent-producing trend in print orders gravitated towards smaller numbers of release prints, making the complex imbibition system less commercially feasible. The first "Star Wars" film in 1977 was probably the last big-budgeted feature made in dye-transfer by Technicolor Labs in England, a company that used the process a few years longer than America, before selling it to the Chinese in 1978. China embraced the dye-transfer process because it made their Communist country less dependent upon foreign suppliers of color film stocks. Many Chinese and Hong Kong production prints were released in dye transfer, among them Zhang Yimou’s famous "Ju Dou" starring Gong Li and even one American film, Richard Haines’ "Space Avenger" (both in 1989). China was able to manufacture the raw stocks required for imbibition printing, but the resultant dye-transfer release prints suffered in image quality due to poor sterile lab conditions and inferior processing, prompting them to discontinue the process in 1993. The very nature of the IB process made it less likely to achieve the degree of sharpness that is possible with the integral tripack films used in modern processing techniques. (I traveled to Beijing Film and Video Lab in 1993 and was allowed to visit their 3-strip printers. Needless to say, the dusty surroundings were less than appropriate for a film laboratory. Although I was not allowed to shoot video, I managed to sneak a few still photos of the lab and its environment.) In 1972, Eastman color print film 5381 replaced 5385 for 35mm end use and 7381 replaced 7385 for 16mm (the first-digit “5” designated 35mm and 70mm acetate film stock and the “7” represented 16mm and 8mm acetate). At this point there was only one common Eastman color print film for all formats. Sadly, film archivists have discovered that the colors in most Eastman prints made from the ‘50s through ‘70s have already faded to a red monochrome. |

|

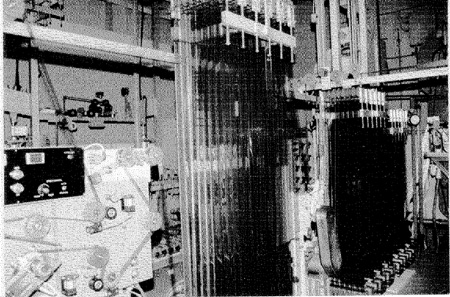

3-strip

dye transfer lab in Beijing, China using Technicolor equipment from England

before it closed in 1993. Photo taken by Les Paul Robley in August of '93. 3-strip

dye transfer lab in Beijing, China using Technicolor equipment from England

before it closed in 1993. Photo taken by Les Paul Robley in August of '93.Often new prints cannot be struck from existing negatives as the colors in these have likewise faded to oblivion. Kodak has since admitted that they had the technology to keep film from fading, but Hollywood didn’t want to pay for it. But now she’s paying in more ways than one, especially when studios discovered the value in releasing older classics on video. The best quality for video transfers still comes from printing from Technicolor negatives onto low-contrast Color Reversal Internegatives (CRIs). An article about the restoration of the 1997 20th Anniversary Special Edition of "Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope" said that even George Lucas went back to his own 1977 IB dye-transfer print of the original "Star Wars" to use as a color reference for the reissue. Lucas confided in the video release: “The original negative had deteriorated a lot more than anyone had expected in 20 years.” Evidently, conventional Eastman color prints of the film had degraded to the point where no two retained the same color balance for the already pink desert sequences on Luke’s home planet of Tatooine. According to Rick McCallum, producer of the Special Edition, “The actual original negative was so far gone that unless we did this at this time, we were never going to have the film to be able to release ever again!” |

|

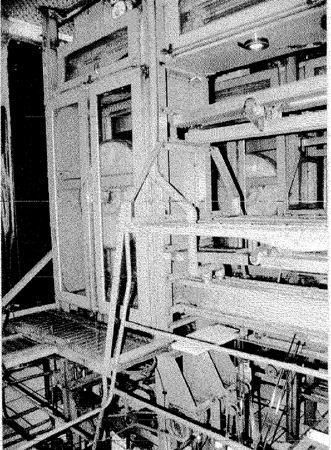

3-strip

dye transfer lab in Beijing, China using Technicolor equipment from England

before it closed in 1993. Photo taken by Les Paul Robley in August of '93. 3-strip

dye transfer lab in Beijing, China using Technicolor equipment from England

before it closed in 1993. Photo taken by Les Paul Robley in August of '93.Interestingly, the consumer market did more to further the advancement of fine grain color negative acetate film than did the professional market. The extended latitude, improved flesh tones and finer grain of Eastman Color Negative II films 5247 and 7247 were a direct result of Kodak’s tiny Instamatic camera craze of the early seventies, just as the 1971 debut of Kodak EKTACHROME 160 Type A Super 8 movie film predated the “existing light” photography for Stanley Kubrick’s famous candlelight look in "Barry Lyndon" (1975). So-called low-fade color stocks were ushered in 1974 to improve the cyan limiting dye-factor with 7/5383 Eastman color SP print film (the SP stood for “Special Process”). Useful for the higher temperature processing ECP-2 for greater release printing efficiency in larger labs, the quality was supposed to be better than the earlier 7/5381 with which it would co-exist (until being discontinued in 1983). Their improved cyan dye was expected to last up to fifty times longer than that of a conventional magenta-stable Eastman print. But even these began to show signs of cyan density loss in the black areas of the transparent image. The color of most SP prints from this period, such as "Superman" I and II (1978 + 1980) and the first Alien (1979), have turned to either a vivid orange or brownish cast, prompting collectors to rename the SP code letters: “Shit Print.” In a properly timed print with good contrast, the black area should be composed of equal densities of the three dye layers. The extent to which the cyan layer has a lower density than the more stable magenta layer in a faded print represents the amount of fading which has occurred in each layer over the years. The RCI-Color Film Restoration Process, invented by Peter Kuran, Sean Coughlin, Joseph Olivier and William Conner (who all received Scientific and Technical Achievement Plaques from the Academy), restored color to faded color negative using off-the-shelf film stocks. The resulting film intermediate can be employed to create a new internegative for making prints. |

|

3-strip

dye transfer lab in Beijing, China using Technicolor equipment from England

before it closed in 1993. Photo taken by Les Paul Robley in August of '93. 3-strip

dye transfer lab in Beijing, China using Technicolor equipment from England

before it closed in 1993. Photo taken by Les Paul Robley in August of '93.Thus, in 1979, Eastman introduced a new LF (Low Fade) print film for 16mm, 7378 and 7379 LFSP film to markedly improve cyan dye post processing dark-keeping stability. Three years later, this would later become Eastman color print film 7/5384 for process ECP-2A, or “LPP” as we collectors have come to know it. It not only improved the cyan dye, but also the red sensitivity to developing variations. LPP was printed along the edge of the film between the date symbols and manufacturing code. It replaced all the previous print stocks and has lasted for 10 years with slight variation (for more information, see SMPTE Journal December 1982 and BKSTS Journal August 1983). The earliest LPP print I own is John Carpenter's "The Thing" from 1982. It has kept its color up to present day stored in a 60-degree Fahrenheit climate-controlled facility in the relatively dry air of Los Angeles. But what does LPP stand for? Why not LFP for Low Fade Print? I called Kodak to obtain some answers. But since Dr. Ryan's demise, no one in manufacturing knew anything about outdated film stocks (unhappily, Standard Operating Procedure in Hollywood). Next, I tried Protek vaults and was informed that LPP stood for Lowfade Positive Print. Bingo! Kodak just made low fade one word. Eastman also produced an LC (low contrast minus 15%) print film 7/5380 for video transfers in 1983 as an optimum reproduction of film for television. It thankfully replaced 7/5738, which was a Lo-Con SP stock from 1977. Rochester later modified 5384 LPP stock in 1988 to eliminate the need for formalin in the stabilizer with process ECP-2B. Formalin retards fading and is like formaldehyde, which is bad for the environment. The 1989 Turner reissue of "Gone With the Wind" was one of the first films to utilize this process. Recall the ballyhoo in the trailer about how this new restoration was bringing the actual colors from 1939 back into the print. (I always wondered why they didn't just reference the old black-and-white separations against an existing I.B. Tech print. Then again, perhaps the variations in color balance between IB prints in general made this procedure inadequate for restoration.) |

|

|

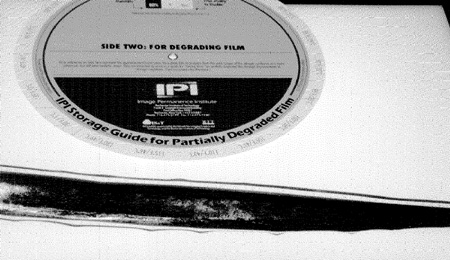

In the early ‘90s, the Image Permanence Institute of Rochester, New York

developed a color wheel in order that archivists could determine how

many years a print would have 30% loss of its least stable dye (usually

cyan, or blue-green) depending on the average temperature and relative

humidity. According to ANSI/NAPM Standards, the recommended range for

extended-term storage of color photographic materials is 20%-50% RH with

temperatures no warmer than 2 degrees Celsius (35 degrees Fahrenheit).

Who but the Library of Congress can afford to store film amid these

climate-controlled conditions? More realistically, the color wheel

storage guide tells users that at an average temperature of 16 degrees

Celsius (60 degrees F) with a RH of 40%, the approximate time to

significant dye fading is 125 years. Raise the temperature by only 10

degrees and that time is cut in half! Another 10 and the fading occurs

in 30 years. The reverse of the wheel depicts a Time-Out-of-Storage

Table predicated on office climate conditions of 24 degrees C (75

degrees F), 60% RH. It is but one example of how the time spent in an

actual use environment modifies the life expectancy imparted to color

print photographs and transparencies out of cold storage. Other use

environments will impact life expectancy to a greater or lesser extent,

depending upon how different they are from the vault conditions. That

same 60 degree F temperature will decrease to 45 years for 30%

significant dye fading when a print is 120 days of the year out of

storage. |

|

Strip

of degraded film on light table with I.P.I. Storage Guide. Notice

crystallization of plastisizers on surface of film. Photo by Les Paul Robley Strip

of degraded film on light table with I.P.I. Storage Guide. Notice

crystallization of plastisizers on surface of film. Photo by Les Paul RobleyUnfortunately a new culprit has emerged to plague older negative and positive materials. Collectors of IB Technicolor 3-strip dye-transfer prints believed they had invested in something that would definitely outlive them in terms of non-fading color and image excellence. Unfortunately, this has not been the case. It turns out that both cellulose nitrate and acetate have a built-in inclination to degrade. Despite the superiority of dye stability in I.B. Tech prints, these films have been found to be more prone to vinegar syndrome (the breakdown of cellulose acetate) than those using standard Eastman color processing. The “smell” gives off an astringent vinegar odor and was first noticed inside a film vault in India where the humidity is extremely high. |

|

Warped,

degraded film showing hex pattern caused by vinegar syndrome. Photo by LPR Warped,

degraded film showing hex pattern caused by vinegar syndrome. Photo by LPRIn addition, IB prints made during the 1950’s 4-track stereo craze—such as "Oklahoma!" - pose a double threat. The magnetic stripe used for the additional sound channels can act as a catalyst in accelerating the vinegar syndrome in these older 35mm mag prints. The iron oxide (like rust) speeds up the chemical reaction, causing these acetyl groups to split apart even more, releasing the acetic acid and subsequent vinegar odor. Keeping the film in a confined state, such as a lab can or shipping case, accelerates the process to the point where the reaction begins to feed on itself, exhibiting an autocatalytic cancer-like behavior. In 1992, Eastman introduced an experimental separation film SO-038 ESTAR stock (SO stands for “Special Order” which was sold as a companion to 5235 acetate) in an effort to offset the problems of vinegar syndrome within black-and-white separation masters for longer storage life. |

|

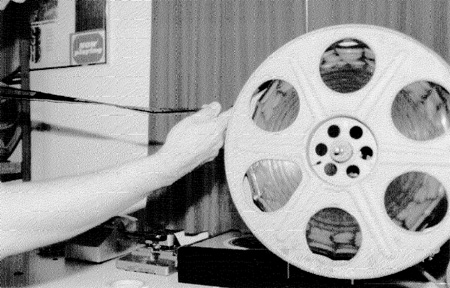

Close-up

of "spoking" hexagon pattern of maximum degraded film caused by vinegar

syndrome. Photo by Les Paul Robley Close-up

of "spoking" hexagon pattern of maximum degraded film caused by vinegar

syndrome. Photo by Les Paul RobleyPolyester (the generic name) is very inert and should last forever, but it hasn’t been around long enough to know for certain. With these prints, vinegar syndrome off-gassing is impossible because they are not acid-based. The film itself is extremely strong and may damage equipment before it tears (one can tow a car with it so keep a reel handy in your trunk). Any stock beginning with a 5 or a 7 is still acetate, and anything starting with SO or 2 is ESTAR. It’s easy to identify since a full reel looks almost transparent when held up to the light. Collectors have often wondered why Technicolor did not revive the older IB process, making it less susceptible to vinegar syndrome using today’s technology, particularly in view of its superior dye stability. There was a time when the dye-transfer process was no longer considered to be commercially viable. The older printing machines were very labor intensive, sometimes requiring eight men to operate one printer. |

|

"Spoking"

wagon wheel pattern of maximum degraded film, showing signs of vinegar

syndrome. Photo by Les Paul Robley "Spoking"

wagon wheel pattern of maximum degraded film, showing signs of vinegar

syndrome. Photo by Les Paul RobleyFor the technique to work in present time, the printers would have to be completely redesigned to be competitive with today’s faster printing processes, and would demand the expertise of individuals who have long-since retired from the film industry. Also, single print orders by low-budget producers would make the process less advantageous due to the amount of work involved in setting up one printer and the cost for ordering the separate matrices. Once that was accomplished, the price-per-footage cost would be roughly the same. For dye-transfer to become feasible again, it would demand a big feature possessing the necessary clout to command a large order of prints. This might initiate a renaissance in the IB process. Happily, A New Hope emerged for dye-transfer’s future, and I’m not referring to the Special Edition release of the first Star Wars. In 1994, Technicolor announced plans to revive an updated version of the 3-strip process perfected by Dr. Kalmus for use with polyester-base film stocks. Three years later, the old IB process was resurrected making fresh prints for selected special engagements of newly restored classics. Reissues of "Giant", "Vertigo", "Rear Window", the full-frame version of "The Wizard of Oz", and "Gone With the Wind" were all re-released in special venues using the dye-transfer method. "GWTW" employed an inadequate reduced-image anamorphic technique to enable its full 1.33-to-1 aspect ratio to be played in today’s modern 1.85 cinemas. Projectionists complained of these prints “shedding” in the gate due to inherent problems with lubrication of the ESTAR-based stock. According to color timer Chris Regan of Deluxe Labs, shedding or “negative/positive skiving” (uneven edges on the film stock) has been a problem with ESTAR. Sometimes, the negative must be rewashed in order to get rid of thin hairline debris caused by skiving that sticks to the emulsion. Since the negative is not disposable (unlike a release print) it must be rewashed. Also, the softer emulsion tends to accentuate its propensity for scratching. |

|

|

In addition, the U.S. releases of "Godzilla", "Bulworth", "Family Man", "The

Wedding Planner", "Bandits",

"Pearl Harbor", "Toy Story 2", and the reissues of

"Apocalypse Now Redux" and "Funny Girl", have all benefited from the use of

dye-transfer printing—not so much for color stability, but in their

respective cinematographers’ decision to enrich the films with deeper,

more saturated blacks. This had heretofore only been possible with the

ENR process which greatly desaturates color. The enhanced Technicolor

process allowed them greater control to deepen specific colors without

affecting the black record of the film. There was little visible density

or contrast change compared to the older 3-strip process. The quality

still matched new Eastman color prints in terms of sharpness, grain,

color and tonal scale. But time was a factor when ordering large numbers

of prints. Of the 6,200 release prints made for "Godzilla", only 1,000

were dye transfer, fifty for "Wizard of Oz" and "Bandits", and a mere

handful for "Pearl Harbor". The age-old method for checking if a print is

IB still involved holding the analog optical soundtrack up to the light

to see if it is black-and-white. Even adjacent digital sound elements,

such as SDDS, SRD and DTS, can have this grayish image. (Recent prints

still possess edge code, usually with the actual date of manufacture—not

symbols. It consists of a different color record so the SDDS sound

reader doesn’t pick-up the latent image. It displays the stock number,

emulsion, roll number, place of manufacture and the year.) Film buffs often wonder why the company failed to promote its revived process. Except for savvy projectionists, management never knew when a dye-transfer print was playing in their cinema. Unlike older posters and trailer ads which boasted the phrase “Color By Technicolor,” only the British film Titus actually mentioned dye-transfer printing in its credits, even when release prints themselves were not IB. Technicolor Corporation seemed to have adopted an over-cautious, nondisclosure approach when it came to discussing current offerings in dye-transfer, almost as if the process was not up to the point where they thought it commercially reliable. In 2001, Technicolor was purchased from British firm Carlton Communications for $2.1 billion by the electronics manufacturer Thomson Multimedia of France, which discontinued dye-transfer in 2002. The Burbank-based company is currently one of the leading manufacturers of DVDs and video games, generating 43 percent of Thomson’s revenue. Now the one-time film giant is on the cutting edge of digital cinema, outfitting theatres to project movies digitally instead of from 35mm film. Two years later, director Martin Scorsese gave dye-transfer a bit of a revival in his film biopic of Howard Hughes, "The Aviator" (2004). He digitally tried to imitate the 3-strip process after newsreel footage of Hughes making the first ‘round-the-world flight. Now the once-film-giant known as Technicolor is on the cutting edge of digital cinema, outfitting theatres to project movies digitally instead of from 35mm film. Eastman Kodak stopped notating stocks as LPP in 1993 with the introduction of Eastman EXR Color Print Film 5/7386. EXR stood for Extended Range and supplied better contrast for scenes shot at night. The last film I’ve seen with the letters LPP stamped on its edge is Steven Spielberg’s "Jurassic Park" (made in 1993, if there are any later ones, please let me know). Now, 5386 acetate film has been replaced exclusively in the labs by Vision ESTAR Color Print Film 2383 and Vision Premiere 2393 (a “clipper stock” with higher contrast). Also, Vision 2395 Lo-con Teleprint Film for video. Acetate negative film is still used for shooting since polyester-based stock can ruin fine camera machinery if it jams. Eastman continues to manufacture intermediate films and some fine-grain black-and-white release positives in acetate, but the bulk of projection prints are on ESTAR 2383 print stock. (Again, any Kodak stock number beginning with a 2 is ESTAR; Fujicolor designates D3513 for ESTAR and Agfa Film is CP30.) Thanks to Dolby, analog SR (Spectral Recording) soundtracks have gone from magenta almost exclusively to cyan-dye track technology. These contain no silver application, eliminating a step in the lab which saves money. SR-cyan tracks are more environmentally-friendly, and remove the possibility of applicator crossing into the picture area on a print. The new cyan analog track must be read with an LED red-reader, as an older white exciter lamp results in very low volume and hiss. In 2007, an Academy Special Plaque was awarded to Ioan Allen of Dolby, Kodak technologists Dick Sehlin and Frank Ricotta, and Tom Kuhn of Deluxe Laboratories, among others, for helping to convert the industry to this new method of laying down analog soundtracks on print film. Since there exists very little recyclable elements in newer films nowadays, most prints are destroyed and used as fuel for a Film Salvage Co. power plant at 4575 Highway 91 N. in Mountain City, Tennessee (what a great place for a film collector to live!). In 2008, Eastman Kodak Company received an Academy Award of Merit (Oscar Statuette) for the development of photographic emulsion technologies incorporated into the Kodak Vision 2 family of color negative films. According to the Academy, “These technologies are breakthroughs in film speed, grain and sharpness that have made a significant impact on the motion picture industry. The Vision 2 family allows wider use of high-speed color negative film, lower light levels on set and faster set-ups. Most importantly, Vision 2 improves the overall picture quality in theatrical presentation.” Also, a Special Plaque went to Jonathan Erland in recognition of his leadership and independent research toward identifying and solving the problems of High-Speed Emulsion Stress Syndrome in motion picture film stock. Kodak still recycles camera acetate stock. But I was informed by a prominent Hollywood facility that most rejected ESTAR lab prints (or release prints that have fulfilled their obligation in theatres) are ground-up and sent to China for reprocessing into polyester for clothing. Just think…That next sweater you buy…You may be wearing an Academy Award-winning print of "Gone With the Wind"! |

|

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|