Dust to Dust

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Robert Wilonsky. From the Week of Thursday, August 9, 2001 . Reprinted from Dallas Observer by permission from Robert Wilonsky. | Date: October 21, 2002 |

Once more, a man calls upon the troops to save

"The Alamo",

before it's gone forever Once more, a man calls upon the troops to save

"The Alamo",

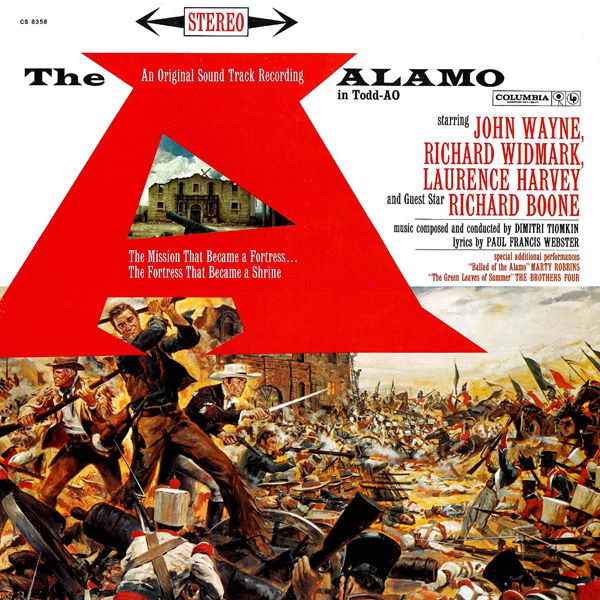

before it's gone foreverTen years ago, Robert Harris picked up the phone to find on the other end a relative stranger bearing extraordinary news. This man was at a film exchange in Toronto, where movies are housed and rented out to exhibitors, and he was holding in his hands canisters of film containing what Harris considered something akin to the Holy Grail: a pristine, uncut 70mm print of John Wayne's initial directorial effort and the Duke's labor of love, 1960's "The Alamo". One imagines it was like a scene from an old film noir, where the detective phones his client with good news: I've got your statue. It's the stuff dreams are made of. Harris was one of those kids for whom movies became glorious instant memories; they were better than real life, because they were so much bigger. He had first seen "The Alamo" when he was 14, at the old Rivoli in New York City, and he never forgot a second of it. "It brought the liberty and patriotism and the whole history of Texas to life," says the man who's never actually visited the Alamo in San Antonio, "and it gave you a whole understanding of what these people were fighting for and what they were up against." "The Alamo" and films like it--sweeping spectacles, old-fashioned roadshow pictures that came complete with overtures and printed programs--made Robert Harris who he is today: the world's best-known film preservationist, a man devoted to protecting such blessed memories before they dissolve forever. That is why this man called to tell Harris he had in his possession "The Alamo"--the entire film, all 192 minutes of it, not the shortened 161-minute version that made the rounds after United Artists demanded it be trimmed shortly after its premiere. It was the only such print in existence, and a mere decade ago, it was in beautiful condition. Harris' new friend wanted to know only how he could keep it that way. Harris made a few calls and arranged to have the movie put in cold storage at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences offices in Los Angeles, but it never made it. Instead, it wound up in the hands of MGM/UA's home-video department, which had it transferred to laserdisc and videotape. Afterward, this once-perfect print was dipped in so-called rejuvenation chemicals, sliced into 1,000-foot sections, dumped into cardboard boxes and put in warm storage, where it sat from 1991 till October of last year, when Harris opened the boxes to discover his beautiful childhood memories lay in near-absolute ruin. Its color was gone; its glory horribly diminished. And it smelled like vinegar, the result of the destructive chemical bath. "They didn't want to ruin it--it just happened--but what happened is unthinkable," Harris says. "The thought of this thing going is just horrible. How do you tell your kids there's no more Alamo? How do you tell the world you've lost a major John Wayne film?" Since piecing together "Lawrence of Arabia" for Columbia Pictures, which re-released David Lean's restored epic in 1989, Harris, along with partner James Katz, has supervised the arduous restorations of such films as Stanley Kubrick's "Spartacus", George Cukor's "My Fair Lady" and Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo" and "Rear Window". All were faded or torn or missing frames and entire scenes (usually, all of the above); all received limited big-screen releases upon completion. Harris not only repaired the damage but worked to make sure those films were seen once more on the big screen, much to the wide-eyed delight of audiences that had grown accustomed to watching such epics and classics on their tiny television sets. His work on "Lawrence of Arabia", which garnered him the support of Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg, made him chief among those who forced studios during the 1980s to realize how shabbily they had treated their pasts by storing old movies in hot warehouses--or, worse, landfills. But never before, Harris says, has he been confronted with the daunting task that sits before him. For the first time since he's been restoring films, Harris is working not just against the unforgiving clock. He also needs money to restore the movie--between $1.6 and $2.6 million, which he doesn't have and which MGM, which owns the rights to "The Alamo", can't pony up. The studio is kicking in a substantial but unspecified amount of cash, but it simply can't afford to invest millions in such an ambitious restoration project. MGM would rather divvy up such funds among dozens of films in need of preservation, rather than just one. As Harris explains, $1.6 million could be spread out among 50 other films that aren't in such horrific shape--Gray Ainsworth, vice president of MGM's technical services, estimates it costs between $15,000 and $50,000 per picture--"so this has got to be back-burner for them," Harris says. Working with the Texas Film Commission, Harris has contacted anyone he can think of about donating money--even Alamo Rental Car, which, he discovered much to his surprise and chagrin, is based out of Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Michael Wayne, the Duke's eldest son, has been contacted, and though he's supportive of Harris' efforts to restore and preserve his father's obsession, the 67-year-old Wayne is too busy raising money for the John Wayne Cancer Foundation. And many of the film's stars--Richard Widmark, Richard Boone, Laurence Harvey, Frankie Avalon--are either dead or living quiet lives well outside of the movie business. Which leaves Harris hat in hand, begging for spare change from any corporation or individuals looking for a tax write-off in exchange for being allowed to use "The Alamo" in promotional materials or for charity screenings. "It's hard to believe I'm sitting in New York worrying about a film about Texas," Harris says. "Maybe the governor can give me a license plate, but all I really want is to sit with an audience in San Antonio and watch The Alamo on the big screen." Initially, MGM asked Harris if he could restore the film for home-video release: The wide-screen 192-minute version is available on video, but the DVD, released last year with the 40-minute "John Wayne's The Alamo" making-of documentary, is the gutted 161-minute version. Harris said it was possible, but the film's in such a terrible state that it couldn't stand being handled more than once, meaning it was an either-or: Either it's fixed up for DVD at the cost of about $1 million--meaning it will never again be available for viewing in a theater, as Wayne intended--or Harris could spend twice that much preserving it forever. "Quite simply," Harris says, "restoring it for home video would have meant we could have never saved it on film, and when I think of "The Alamo", I think of it as that 14-year-old kid in a movie palace watching John Wayne and the Texicans trying to save the Alamo." As Harris describes it, the movie, as it exists now, is bereft of any color save for one, green. And the facial highlights all look distinctly "crustacean," he says, because there's no blue left in the print or the original negative. The film also flickers throughout, the result of the chemical bath it received a decade ago. All that remains fully intact is the soundtrack, which is currently being preserved by MGM at the Todd-AO sound studios in Los Angeles. Ainsworth says The Alamo is not "in imminent danger" because it's being kept in the proper cold-storage facilities, but Harris doesn't want to wait. In order to restore the film, he and MGM have two options: The "lost" 31 minutes will be lifted from the faded print, but the bulk of the film can either come from the original 65mm separation masters (a preservation element holding a third of the color spectrum on three strips of black-and-white film) or the digitization of the original 65mm negative (some 45,000 frames, each treated like an individual photograph). If it's the latter, they will restore the color using computers, then output the entire thing onto a brand-new 65mm negative. The process will take a good two years, but the result will be invaluable: "The Alamo", in its entirety, will last for hundreds of years. "The Alamo", though, is but one of hundreds of landmark films deteriorating in cold-storage vaults around the country; not until the 1980s, when Columbia released "Lawrence of Arabia", did studios think enough of their old movies to protect them from time and the elements. Indeed, more than half the films made before the 1950s don't exist at all, either because they've dissolved to dust as a result of film stock and chemical treatments or were tossed out by studio execs who simply needed the storage space. The studios have made concerted efforts to atone for past sins, but if you wanted to walk into a theater and watch an immaculate version of "North by Northwest", "West Side Story", "Ben Hur", "The Godfather", "South Pacific", "Carousel" or "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World", it would be impossible. They simply do not exist. "The Alamo" hardly ranks among Wayne's best films; it's overwrought, lethargic and jingoistic to the point where its history isn't even accurate. Wayne himself was overwhelmed by the entire production: He begged for money (which, perhaps, makes Harris feel a special kinship with the Duke) when studios resisted his desire to direct, found himself wrestling with the extensive, expansive action sequences and had to fend off John Ford's interference when the director showed up on set uninvited. Harris would admit it's not one of the greatest movies ever made, despite its Oscar nomination for Best Picture. But that matters little to the 14-year-old boy who fell in love with Texas from the inside of a New York City theater 41 years ago. "Is "The Alamo" one of the great films?" Harris asks. "No. Wayne himself said it was full of speechifying. But to my mind, it's the consummate image of American patriotism and heroism and the birth of Texas. I still remember seeing that film as a 14-year-old, and how do you let something like that get away from you so kids can't see it again? You can't." |

Further

in 70mm reading: The Reconstruction and Restoration of John Wayne's "The Alamo" "The Alamo" lost 70mm version - This letter which started it all Remember "The Alamo" Remembering Dimitri Tiomkin |

| Go: back

- top - back

issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|