A Nostalgic View of 70mm in New York City 1950-1970 |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Jonathan Kleefield, M.D., Newton Center, MA, USA | Date: 18 May 2005 |

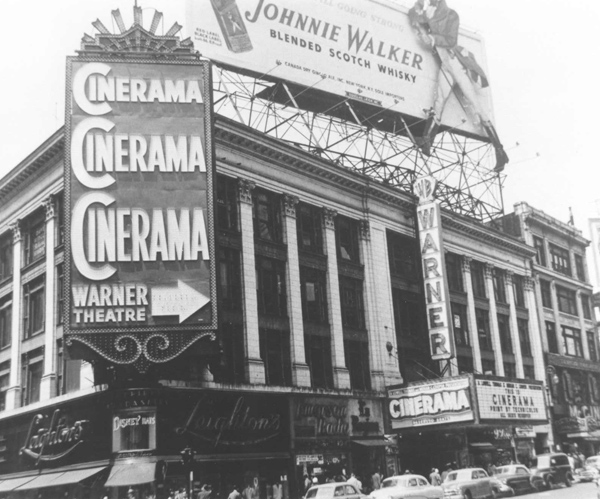

"This

is Cinerama" at the The

Warner Theatre, New York, 1953. Image: Cinerama Inc. from the Willem Bouwmeester archive "This

is Cinerama" at the The

Warner Theatre, New York, 1953. Image: Cinerama Inc. from the Willem Bouwmeester archiveAs a matter of introduction, I am an unabashed cinephile. My fascination with film began in 1950, when as a five year old child, my grandmother introduced me to this medium, via a trip to our local movie house, the Forest Hills Theatre. This establishment, built in approximately 1920, did not have facilities for 70mm projection, but its screen and reasonably good 35mm film chain hosted a film which left an enormous impression upon a youngster like me. It was George Pal’s science fiction film, "When World’s Collide", made for Paramount Pictures. This Technicolor extravaganza portrayed an apocalyptic end to the world, caused by another planet hurtling inexorably on a collision course with Earth. The frantic preparations of the citizenry to attempt to hide from this catastrophe, the monstrous alterations in the weather, including tidal waves sweeping Manhattan island, as well as the fortunate few who managed to board a space ship to escape certain death, made it clear to me that film could create any illusion desired, and be a most effective means to generate a profound emotional response from its viewers. • Go to Eighteen Years Later • Go to "Oppenheimer" Reviews From then on, whenever a break from my normal studies occurred, I immersed myself in reading about film technology, even to the extent that I insisted my mother read articles about motion picture production to me at bedtime. My little sketchbooks were filled with crude renditions of Mitchell BNC cameras, Western Electric and RCA 77DX microphones on booms to capture the scenes of a film in production. In 1952, that same wonderful grandmother brought me into Manhattan, where we sat together in the Warner Theatre. The curtain parted, revealing Lowell Thomas discussing existent film technology. The image of this famous reporter/adventurer was roughly the standard Academy aspect ratio, A few minutes later, he intoned the now famous phrase “And this is Cinerama!” At that moment, the curtain parted to reveal an enormous curved screen, which essentially filled our field of vision, and depicted the climb up the first hill of the Rockaways Playland Roller Coaster, called the Atom Smasher. Immediately, the audience responded with gasps, groans, and a few shrieks, which intensified when the coaster reached the summit of the first hill, and began to accelerate and dive down a long steep drop. The eye-filling image, supplemented by Hazard Reeves’ extraordinary 7 channel sound system, including a then-very convincing surround effect, all recorded on separate 35mm magnetic film, was simply an unprecedented, thrilling sensation. In the intermission, I managed to get a look at one of the three synchronized projectors needed for the show, including the titanic 8000 foot reels required to run the film continuously up to intermission, making it necessary to provide synchronization only twice (for parts 1 and 2). Despite using three 35mm films, the composite image appeared quite “seamless.” However, even to a novice like me, I could not imagine a setup this complex ever finding its way to the Forest Hills Theatre. Neither did one of Cinerama’s backers, Mike Todd. It seemed to him that it would be a much more likely scenario to bring large screen movies to a wider audience if, as he was quoted to have said that he could get “Cinerama outa’ one hole,” namely a single film projection system. |

More in 70mm reading: Eighteen Years Later The Ziegfeld has closed Radio City Music Hall Rivoli Theatre Syosset Theatre 70mm Cinemas in North America Presented on the big screen in 7OMM Todd-AO Paul Rayton Remembers "Scent of Mystery" 19. May 2005 Hi Thomas! It looks fantastic, and I am SO grateful- in effect this is my birthday present, as I will have said anniversary tomorrow (5/19). I appreciate your kind words, and the beautiful photographs adorning the article, particularly the famous image of Gloria Swanson amid the ruins of the Roxy. Each birthday brings waves of nostalgia to me. I do miss those wonderful experiences in real cinemas, not the boxes of today, sans curtains and the like. Please keep in touch, and kudos to your wonderful efforts. PS- there was a wonderful program on our public television station regarding a Mitchell standard movie camera bought by Sam Dodge in Washington state. which turned out to be owned by Eddie Lindon, and used for the filming of "King Kong" (1933 version). The camera is a thing of beauty, and its story was fascinating. Jonathan |

The

Rivoli on Broadway, New York, October 1955. Image by Don Whitney The

Rivoli on Broadway, New York, October 1955. Image by Don WhitneyI have read about the life and times of Mike Todd, and his determination to reach his goal, through his efforts with Dr. Brian O’Brien of the American Optical Company. Todd financed their research to produce a series of optics that could do justice to the task of painting an image on a film stock double the width of 35mm, i.e., 70mm, which would also include a 6 channel magnetic sound track array on the film stock itself, as opposed to a separate sound-only film. I know that Todd was fortunate to have acquired some rather antique 70mm Thomascolor cameras, retooled by Mitchell, as well as Fearless cameras, which were initially manufactured for some early Hollywood experimental features, with the films identified by names such as the “Real Life” and “Grandeur” processes. But, like early quadraphonic sound in the 1970’s, these efforts were short-lived, likely in part due to the Depression, with the cameras then being placed in storage, as well as an apparent lack of approval by the viewing public of that era. Meanwhile, 20th Century Fox moving forward with its introduction of the French anamorphic process, christened CinemaScope and premiered in 1953 with the film, "The Robe". The ability to inexpensively convert existing 35mm projectors to show these films, via the Bausch and Lomb supplemental lenses, ensured its quick implementation. However, I don’t remember being particularly impressed with the early CinemaScope productions, despite the participation of Marilyn Monroe. (I guess I was far too young to appreciate her “charms.”) I can’t recall being aware of the optical distortion caused by inconsistency of the anamorphic squeeze, resulting in what was affectionately called CinemaScope “mumps.” Nevertheless, many of the films, now projected essentially double their original size, looked grainy, dimmer, and lacked the “sparkle” and “punch" of their 35mm forebears shown in the Academy ratio. My tenth birthday was in 1956. As a present to mark the occasion, my mother (this time) took me and my cousin William, again into Manhattan, but now to the Rivoli Theatre, on 49th St. and Broadway, to see the recently premiered "Around the World in 80 Days", a Mike Todd production. The theatre was medium size, ornately decorated with somewhat “classical” friezework, and with a relatively short distance between the screen and the rear of the theatre. As the houselights dimmed, I was thrilled by the stirring Victor Young overture, played over a wonderful multichannel sound system (likely with Voice of the Theatre speakers). When the curtain parted, once again at Academy aspect ratio, Edward R. Murrow, the celebrated CBS radio and television commentator, described the yearning of Man to travel faster and faster. He narrated the George Melies 1901 film dramatizing Jules Verne’s story "From the Earth to the Moon", and informed the audience that it was the first production to use lap dissolves and multiple exposures. At the end of his prologue, the curtain opened, once again to reveal a giant, deeply curved screen depicting a rocket launch at White Sands, New Mexico. The deafening sound of the launch was effectively reproduced, following which the entrancing film began, depicting the Mexican star, Cantinflas riding his bicycle down a London road. I remember noting that horizontal lines, such as streets, in the image were curved upward at either side of the screen. I thought this was a consequence of our being seated far to the right of center, but I have later learned that the problem may have been due to the projector being located higher than the screen, causing a keystone effect which distorted the image. I cannot remember whether this was actually the case when I saw the film, but I have learned that the projectors in the Rivoli were subsequently placed in the Mezzanine, nearly level to the screen. What I remember clearly was that the picture quality, namely screen image stability, brightness and clarity were unprecedented. Certainly, using a 30 fps projection speed was very helpful in diminishing flicker. But, of course, this was my first experience with 70mm film projected by the Norelco DP70! This extraordinary device had no peers at the time, and for many years to come as well, perhaps only being supplanted when IMAX perfected its large format 70mm behemoths. The film was so wonderful that I returned at least three more times to watch it during its engagement at the Rivoli. From that time on, I bought the costly ($3.50 USD!) tickets myself, being extremely careful to have an ideal, perfectly center Orchestra seat, and just close enough to have the screen essentially fill my field of view. While the optical distortion mentioned above was likely unaffected by my prime seating position, and I later became acquainted with the barrel distortion caused by O’Brien’s 12.8mm “Bug Eye” lens, particularly evident in the scenes at the Spanish bull ring, it didn’t detract from the spectacle and pure fun of this presentation. Several years later, I saw the film in CinemaScope while touring Minneapolis, Minnesota, and felt that an “old friend” had not been treated well by being taken out of the equivalent of a mink coat (70mm) and put in a shabby smock (35mm CinemaScope). There was simply no comparison. (I never saw “Oklahoma!”, the first Todd AO 70mm film when it had its 1955 debut, nor the CinemaScope version shot simultaneously.) My next 70mm encounter was the film "South Pacific", which I believe debuted at the Criterion Theatre in 1958. This film venue had a relatively modern interior, with what I remember was primarily crimson-colored walls, carpets and seats, and with excellent sight lines. This superb Rogers and Hammerstein musical, with book by James Michener and direction by Josh Logan, was filmed in Hawaii, with key scenes on the island of Kauai (from which I have just returned, it being my fifth visit to that magical place). While some urbanization of Kauai has occurred in the nearly 40 years since this film was made, it has been relatively slow, compared to Oahu or Maui. The beach at Hanalei was prominently featured. However, I remember being appalled by what was done to the film, supposedly in the name of creating “atmosphere.” As most of the songs began, the film laboratory was instructed to dye the image, as if a “wave” of color was suffusing the picture. Such an effect may have worked once, or twice, but used repeatedly it proved a hideous distraction. No amount of great music, beautiful sound, and even a Todd- AO format could rescue this presentation for me. Also, I remember that the screen was not particularly curved, which further degraded the image, but not nearly as much as that awful distortion of what could have been magnificent Technicolor photography of unimaginably beautiful scenery. |

|

The

famous image with Gloria Swanson in the ROXY rubble October 14, 1960. Picture by Eliot Elisofon,

LIFE Magazine The

famous image with Gloria Swanson in the ROXY rubble October 14, 1960. Picture by Eliot Elisofon,

LIFE MagazineAlso in 1958, as a celebration of my being elected to the Honors Society in my middle school, my parents took me to the film "Windjammer", which I believe was shown at the Roxy Theatre. That fantastic, rococo-style venue was the largest motion picture palace ever constructed, and which held 6218 people! The film process was “Cinemiracle”, which was billed as a superior version of Cinerama, but again using three 35mm images. Instead of a “gigolo” blurring the seams between the panels, mirror optics provided an improved connection between the individual sectors of the composite picture. Again, a very deeply curved screen and multichannel sound were very supportive of this film, which depicted the voyage of the Norwegian training ship “Christian Radich”, as it plied the seas and fjords around Scandinavia. (Subsequently, I was able to view this beautiful vessel while it was docked in Oslo harbor, as part of a memorable 1967 trip to Norway.) The climactic scene was a performance of Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto, accompanied by our own Boston Pops Orchestra, led by Arthur Fiedler. I remember thoroughly enjoying this film with my parents, and for years held on to the souvenir book we bought that night. My relationship with 70mm resumed in 1959, first by attending the ill-fated film "Porgy and Bess", which I believe debuted at the Warner Theatre. This was a Todd-AO format film. Sam Goldwyn’s production was nearly terminated when a huge fire destroyed the Catfish Row set, and with a number of accidents plaguing its principal players during shooting. I do remember that Sidney Poitier, who played Porgy, was reportedly unable to even sing “Happy Birthday” on key, so his singing was dubbed by Robert McFerrin, Bobby McFerrin’s father and a famous opera singer of the time. While I have subsequently learned that the film was deemed a failure by critics, I was moved by the fantastic score, expertly rendered under the supervision of Andre Previn and Ken Darby, and through a wonderful sound system. The Todd AO photography and projection I felt were very impressive, and could easily convey both scope and intimate moments with great visual power. Sadly, I have never been able to find this film on any medium ever again, even when I had the opportunity (and thrill) to speak to Maestro Previn himself, during one of his visits to Boston as guest conductor of our Symphony orchestra. Of course, like so many others, I remember that the widescreen majesty of first-rate 70mm projection was fully realized when I attended a screening of "Ben Hur", in the latter part of 1959, at the sumptuous Loew’s State Theatre. This fantastic film was shot in MGM Camera 65, which I have learned is a format virtually identical to Ultra Panavison. While I cannot clearly remember the displayed aspect ratio, the image was certainly large, vivid, and superbly illuminated, presumably courtesy of perfectly maintained DP70’s. However, I do remember that the screen was flat, which I thought detracted from the illusion of stereoscopy so wonderfully suggested by the Todd-AO process. Very memorable was the use of the surround speakers, particularly when Judah Ben Hur finally reunites with his mother and sister, who by then were scarred by the ravages of leprosy, only to be miraculously healed by the Lord, to the strains of Miklos Rosza’s stirring orchestral score and chorus at full tilt!. Charlton Heston never had a better vehicle for his talent (and handsome demeanor), despite the 1956 VistaVision epic, "The Ten Commandments" which allowed him to play Moses and be directed by Cecil B DeMille. In my opinion, William Wyler, who directed Ben Hur, made a far more exciting movie, particularly when Heston goes nose to nose with the evil Messala, played by Stephen Boyd, in the now-legendary chariot race scene, during which one $100,000 Camera 65 unit was smashed into smithereens by an errant chariot! In 1960, I saw "Exodus", and in 1961, "West Side Story". Both were Super Panavision 70 films, with "Exodus" screened at the Warner Theatre and the Leonard Bernstein musical classic at the Rivoli. Once again, image quality, particularly the rock-steady picture, strong illumination and resultant vibrant colors were impressive in both films, with the musical having a very fine sonic presentation. But once again, I yearned for the curved screen to provide that illusion of depth. Just recently, I picked up DVD’s of both films. "Exodus", at present, is on a DVD that is not transferred anamorphically, with resultant abysmal image quality. In contrast, "West Side Story" has been transferred with great care, and the film comes alive once more with great power on our 50 inch Panasonic plasma TV and surround sound apparatus. Not quite 70mm, but a lot more comfortable (as we have installed our “theatre” in our boudoir!). However, 1962 was a milestone- it was the year that "Lawrence of Arabia" premiered, and of course, I had the privilege of attending this presentation at the Criterion Theatre. While the format used was Super Panavision 70, and no curved screen was employed, the impact that this film made on me was simply staggering. The quality of Fred Young’s cinematography, exemplary sound and the Maurice Jarre score, and of course, David Lean’s direction, made for an overpowering experience. The cavalcade of stars provided ample support for the stunning screen debut of Peter O’Toole, who I think gave the defining performance of his life! I cannot tell you how many times I returned to see this film at the Criterion, but all-told, including the revival in 1989, here in Boston, it must be over a dozen times that I have seen this amazing presentation. Although I have both DVD versions, they cannot deliver anywhere near the image detail emblematic of 70mm at its finest, and believe me, the Criterion staff “delivered” on this promise completely! I entered university that same year, and with my studies occupying a good deal of time, did not attend 70mm films for a brief period. However, I did get my first chance to actually view the DP70 while travelling to Denver, Colorado in 1963. The film being shown was "Cleopatra". While the extravagant anatomic proportions of Elizabeth Taylor were well served by the 70mm format, I remember the film was anything but exciting. Thus, I journeyed to the balcony, to find the projection booth door ajar. I was warmly greeted by the projectionist, and invited to enter his kingdom. In short order, we became friends, to the extent that I was allowed to view the projection process and given a 2 foot long piece of 70mm leader film, which I kept for nearly 20 years as a precious souvenir of my trip. By 1964, academic life had settled down enough for me for time to view "My Fair Lady", again using the Criterion Theatre, as well as the John Ford film, "Cheyenne Autumn", shown at the Loew’s Capitol Theatre. I do not recall being particularly impressed with the presentation of the Lerner and Lowe musical, although I have subsequently viewed this film in high definition on our plasma TV, courtesy of the HDTV cable outlet, HDNet. The film was completely shot in a studio, and the beautiful costumes were quite impressive, but I don’t think particularly enhanced by the large screen presentation (it looked great on our high definition TV, though). By contrast, the John Ford epic was filmed in his favorite location, Monument Valley, in Utah. That spectacular scenery could not have been a better vehicle to showcase the supremacy of 70mm. This film, as well, was shown on the same high definition channel this past year, and seeing it once again confirmed my recollection of how impressive it looked when properly projected (which it most certainly was at the Loew’s Capitol, another wonderful large scale Manhattan theatre). Another “detour” of sorts also occurred in 1964, as my home in Queens, New York, was only a few miles from the site of the New York World’s Fair. Thus, I was able to repeatedly attend this terrific attraction, many of whose exhibits were based on film presentations. The 70mm films I believe I viewed included Billy Graham’s "Man in the 5th Dimension", but few details regarding the venue or the film itself am I able to recall. The film that did make an impression upon me was the United Air Lines presentation entitled "From Here to There". It was a showcase for the geographical beauty available for view via flying, with the director Saul Bass mounting a camera in the belly of a 707 jet, which flew across the United States. The images of the terrain below, depicted essentially from a vertical vantage point, were reminiscent of abstract art, a vision entirely appropriate for a man who was known at the times as the premiere producer and designer of film title work. |

|

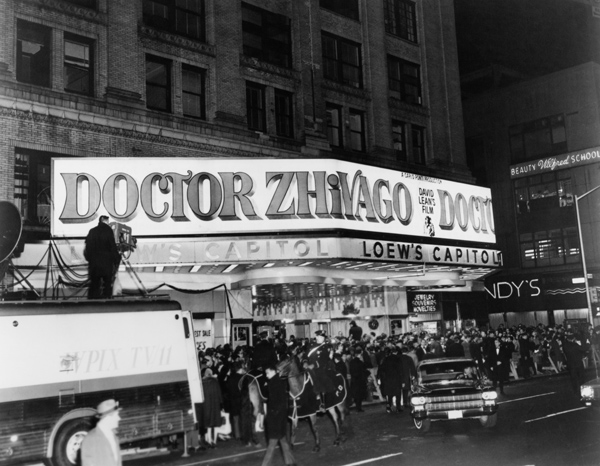

Gala

New York World Premiere 22 December 1965. Picture: MGM Publicity, 1965. Gala

New York World Premiere 22 December 1965. Picture: MGM Publicity, 1965.In 1965, David Lean once again provided a film worthy of 70mm, which I saw shortly after its New York premiere at the Loew’s State Theatre. This, of course was "Doctor Zhivago". Fred Young’s camera and lighting simply fell in love with Julie Christie, and made an instant star of Omar Sharif, despite his very memorable preceding performance in "Lawrence of Arabia". I was awed by the picture quality, but even more so when years later I learned that the film was originally shot in 35mm and “blown up” by the MGM lab for 70mm “roadshow” presentation. What is particularly amazing is the fact that the producers forced Lean to shoot in 35mm to save money on film stock! How fortunate all concerned were that the laboratory worked a miracle, and even a “seasoned” viewer such as myself was not aware that I was not really viewing a “pure” 70mm presentation. By 1966, I had graduated university, and went to medical school in Philadelphia. While I saw occasional 70mm films, such as "Grand Prix" and "The Sound of Music" in houses down there supposedly designed to properly showcase these films, I decidedly remember that the presentations were inferior to those I had the privilege of viewing while a resident of New York City. In 1968, while on vacation back in New York City, I saw Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece, "2001 A Space Odyssey", at the Loew’s Capitol, which fully exploited the panoramic potential of Super Panavision 70. The film’s heavy symbolism, as well as the extended optical abstract art concluding the film, were difficult for me to comprehend, but the gorgeous astronomical special effects were stunning. Later that year, a classmate and I viewed "Oliver", a musical shown at the Loew’s State, and again, a laboratory “blow up” from 35mm. Once again, the lab triumphed, and the lively presentation was very enjoyable. My 70mm sojourn in the New York City area ended in 1970, with the D-150 presentation of "Patton", this time at the beautiful, modern Syosset Theatre, in Long Island. I felt a great sense of nostalgia, as if drawn back to the earliest days of my wide screen experience, as the D-150 process employed a deeply curved screen. Viewing this film proved to me that a “participatory” viewing experience is truly facilitated by this screen configuration. George C. Scott’s brilliant performance served as the culmination of this truly memorable portion of my cinematic life. From time to time, I’ve been able to take in a few 70mm films after those golden years in New York- e.g. "Star Wars", or the revival noted above of "Lawrence of Arabia". But to be sure, nothing has or will surpass the pleasures I was afforded during the nearly 20 year period when I witnessed the birth of truly memorable film presentation in New York City, in glorious 70mm! |

|

|

Go: back

- top -

back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|