1930's Large Format Equipment at the USC

Archive |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Dan Sherlock, 2005, with some 2015 updates | Date: 05.06.2016 |

Dan

Sherlock and a Fearless 65mm film magazine. Picture by Paul Rayton Dan

Sherlock and a Fearless 65mm film magazine. Picture by Paul RaytonThe University of Southern California has one of the most respected schools of cinema-television in the world. Many famous directors, cinematographers, editors, and others involved in the production of motion pictures and television programs learned their craft at this school. Located below one of the buildings is the USC Moving Picture archive. The archive includes over 18,000 student films, 35mm films, magnetic elements, video tapes, posters, screenplays, cameras and projectors. It takes someone with expert knowledge of the cinema to care for all of this – someone who not only knows about the studios and people, but who also knows about the technology behind the materials and equipment used to record and present the images and sound that comprise cinema and television. USC is lucky enough to have such a person. Herb Farmer is a Professor Emeritus at the school and has been teaching there for over 30 years. But he is also in charge of the archive, and looks after it with pride and the love of cinema that permeates his being. He not only loves his work, but he is a virtual fountain of knowledge. The archive includes dozens and dozens of cameras, projectors, tripods, blimps, and other items dating back to the earliest days of the cinema. The equipment was acquired and donated by many people, including Mark Serrurier (inventor and manufacturer of Moviola editing equipment), Sidney Solow, (President of Consolidated Film Industries and for many years a regular lecturer on laboratory and film processing), Sol Lesser (film producer), Robert Nichols (heir to Art Reeves who was a founding ASC cameraman with a sizable equipment collection), and Earl Sponable who was one of the chief technical people at 20th Century-Fox from the 1920's until the 1960's. Hundreds other individuals have also donated items to the archive. With all of his hands-on experience with much of the equipment used for filming and showing motion pictures, it isn't often that Herb Farmer comes across items which are unknown to him. So when he offered to let a few people take a look at some old large-format cameras and projectors and equipment to help figure out what they were, it was obvious that the equipment was truly unusual. The lucky people that got to see this equipment in November of 2004 were Dan Sherlock – systems engineer and film format historian; Rick Mitchell – director, film editor and film format historian; John Hora, A.S.C. – cinematographer and 70mm film advocate, and Paul Rayton – projectionist at American Cinematheque's Egyptian theater and also a 70mm film advocate. |

More in 70mm reading: Gallery: "Antique" Wide-Gauge movie cameras and projector equipment at the University of Southern California - Department of Cinema/Television Introduction to Projection and Wide Film (1895-1930) An Homage To D. W. Griffith "Panorama Blue" in 70mm Magnified Grandeur Internet link: |

The Large Format Systems of 1930 |

|

John

Hora (ASC), Rick Mitchell and Dan Sherlock. Picture by Paul Rayton John

Hora (ASC), Rick Mitchell and Dan Sherlock. Picture by Paul RaytonDuring the development of the large format processes around 1930, several different formats were experimented with by various studios and individuals. William Fox had purchased the rights to use a 57mm format called Widescope which used a pivoted lens to record a wider-than-normal field of view. Fox and others worked at improving the camera, with William Fox receiving some patents on improvements to this camera. But at the same time, he asked his chief technical assistant Earl Sponable to try to develop a simpler camera and format that could achieve a wide screen and a wide field of view. This second process became what is known as Grandeur – a 70mm format with larger-than-normal perforation holes and a longer-than-normal perforation pitch of 0.234 inches. Because of the longer pitch, the frame on the film was four perforation holes high even though the image was about 25% taller than the silent aperture 35mm format. William Fox apparently decided to go with the Grandeur format rather than the Widescope format and his studio made a number of films in the process, including Fox Movietone Follies of 1929, Happy Days, The Big Trail, and a number of newsreels. The MGM studio, which William Fox acquired the control of in early 1930, adopted the use of the 70mm Grandeur cameras but elected to use 35mm reduction prints for exhibiting the wide screen image and referred to the format as Realife. MGM also elected to use a larger area of the 35mm film by cropping the image recorded by the Grandeur camera to a narrower 1.75:1 aspect ratio. Fox had the Mitchell Camera Company create a 70mm version of their popular 35mm camera. This 70mm camera looked almost identical to the 35mm camera but was just a little bit larger. Stein Camera Company in New York also made some much larger cameras for Grandeur. This camera was later modified in the 1950's to become the first camera design used for CinemaScope 55. Fox supposedly also had the Wall Camera Company in New York make some Grandeur cameras, but no photographs or examples of this camera have been found. Kodak made the film using perforators loaned to them by William Fox. International Projector Corporation made the initial prototype projectors as well as the final "Super Simplex" projector design. RKO teamed with George Spoor to utilize the 63.5mm Natural Vision format for the feature film Danger Lights. The cameras and projectors were made for Spoor in Chicago. But the Natural Vision format was developed during the silent era, and the modifications needed to show the format with sound made the process impractical for most theaters. So RKO also investigated the use of other formats which might prove to be more practical. |

|

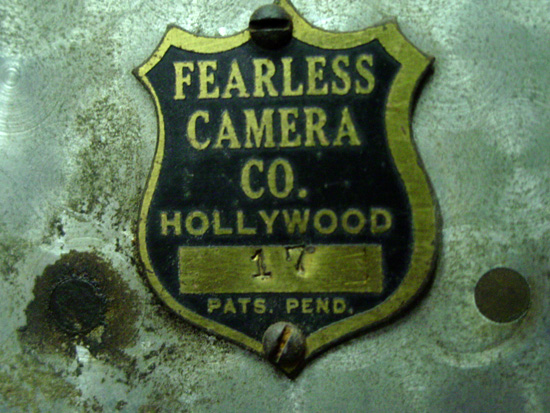

Fearless

Camera Co.

number plate. Picture by Paul Rayton Fearless

Camera Co.

number plate. Picture by Paul RaytonParamount developed a 56mm format called Magnafilm which was basically the same image height and film pitch as conventional 35mm film, but with the use of wider film to achieve a 2:1 aspect ratio. The format was used for an industry screening of a short subject called You're In The Army Now in 1929. There were problems evident at this showing, including a falloff in brightness at the corners of the frame and some focus problems throughout the first reel of the presentation. Those problems along with the difficulty in making a projector that could handle both 56mm Magnafilm and conventional 35mm film caused Paramount to abandon the process. The most widely adopted large format process of 1930 was a 65mm format. The format used the same sprocket hole and pitch as 35mm film, but with a frame five perforation holes tall. Thus it achieved about the same size image as Grandeur but with a conventional sprocket hole size and pitch. It is not clear who originated the format, but several studios and equipment manufacturers adopted the process. The Fearless Camera Company developed and sold the Fearless Super-Film 65mm camera, which could also be adapted to use 35mm film. Warner Brothers called the format Vitascope, and developed their own camera and two different projector designs. Warner Brothers used the Vitascope format for a short subject called the Larry Ceballos Review and the feature films Kismet, A Soldier's Plaything and The Lash. Universal announced they would adopt the 65mm format and call it Magnachrome, but nothing seems to have been exhibited by them using the process. Paramount, having abandoned the 56mm Magnafilm format, had Andre Debrie in France make a 65mm camera. Test footage was shot with the camera, but it was never used for a publicly exhibited film. United Artists used the 65mm format and called it Magnifilm for wide film version of The Bat Whispers. There is still a lot of debate as to which camera design was used for this feature film. The Fearless Super-Film camera was available for purchase and was an excellent design. Another report was that a 65mm camera was made for Spoor in Chicago and wound up being used. Mitchell Camera Company claimed to have modified a 70mm Grandeur camera to use the 65mm standard for use on the movie, and research has confirmed camera serial number 6521 was completed on July 1, 1930 and delivered to Feature Productions. Feature Productions was the production company used by Joseph M. Schenck who had produced the earlier feature film The Bat, and he was also the producer of The Bat Whispers. And there is always the possibility that multiple camera designs were used. Besides the 65mm Warner Bros. projector designs which were used exclusively in their theaters, Fearless developed a modification to existing Simplex projectors for 65mm that could be installed for less than $300. The Ernamenn company in Germany made some 65mm projector mechanisms for Paramount to use in their 65mm experiments, even though very little information about the equipment was published. |

|

The Projectors at the Archive |

|

German

Ernemann 70mm projector. Image by Dan Sherlock German

Ernemann 70mm projector. Image by Dan SherlockThe first thing we examined were two Ernemann projector mechanisms which were made about 1930. We already knew that old Ernamenn projectors from about 1930 were used during the development of Todd-AO in 1953 to view the test sequences. What we examined, however, could probably be better described as "projector mechanisms" since there were no reel magazines, no pedestals, no lamphouses, no lens mounts, no shutters and no motors. However, they bore a strong resemblance to the projector mechanism shown in the February 1931 issue of the Journal of the S.M.P.E. One of the projector mechanisms had sprockets designed for 65mm film. A piece of modern 70mm film was fitted against the sprocket to confirm that the size and spacing of the sprocket teeth were the same as the standard used by Todd-AO and later 70mm formats. It also confirmed that there was enough clearance to allow the 70mm width, which might be an indication that there was some thought given to modifying the design if the 70mm format based on Grandeur became a prevalent standard. It also confirmed that if this was the projector design used by Todd-AO in 1953, then it would have required very little modification from its original design to use the wider 70mm film used by Todd-AO as well as the 65mm format. |

|

German

Ernemann 70mm projector with dual format 35/70mm sprockets. Image by Dan Sherlock German

Ernemann 70mm projector with dual format 35/70mm sprockets. Image by Dan SherlockThe second Ernemann projector mechanism was similar to the first except that the sprockets were made to take either 65mm film or 35mm film. It had become apparent to exhibitors in 1930 that if wide film was going to be adopted, it would be necessary to have a projector that would work with both the wide film format as well as 35mm film using either the full "silent" aperture or the optical sound aperture configurations. Although neither of these projector mechanisms were fitted for optical sound reproduction, the design appeared to account for the optical track area. For example, one of the rollers had a recessed area that corresponded with the sound track area. |

|

The Large Format Camera Magazines |

|

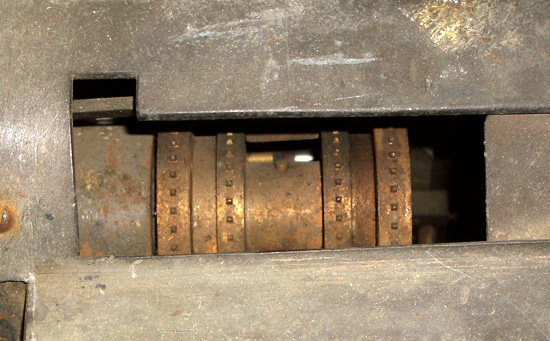

65mm

magazines. Image by Dan Sherlock 65mm

magazines. Image by Dan SherlockWe next examined three different types of large format camera magazines. The first was immediately recognizable as magazines for the Fearless Super-Film camera that was introduced in 1930. This camera was a very versatile camera that considerably reduced the amount of noise made by the camera compared to other cameras of the time. The camera was designed for the 65mm format that some of the studios were adopting during 1930, but it could also be modified to work with smaller gauges including conventional 35mm film. The first thing checked with the Fearless magazine was if 70mm wide film could fit through the film opening, which would imply that the camera could possibly have been adapted to the 70mm Grandeur format if necessary. However, examination of this opening confirmed that it was too narrow to allow 70mm film to be used, and the magazine itself too narrow to permit modification for the use of 70mm film. Thus, it appears that stories about the Fearless camera being adaptable even for 70mm Grandeur appear to be false, or else the stories actually meant that a new design based on the concepts used in the 65mm camera could be made. The Super-Film magazine is documented in U.S. Patent 2,007,468 published in 1935. This patent shows the magazine being mounted to the camera via either a long screw located between the reels, or using a threaded hole located towards one side which would allow a thumbscrew to retain it to the camera. However, the actual magazines use only the offset threaded hole and do not have the central long screw shown in the patent. |

|

65mm

magazines. Image by Dan Sherlock 65mm

magazines. Image by Dan SherlockThe Fearless Super-Film camera and its 65mm magazines would be adapted to an 8-perf advance in the1930's and used for the experimental Thomascolor process, which used three areas (and later four) that were approximately the size of conventional 35mm images to produce a three-color additive system. The Thomascolor cameras would be returned to their original 5-perf advance and have the camera apertures widened in late 1952 to become the first Todd-AO cameras. These cameras were used for the first two Todd-AO feature films and for a number of other productions, including some shots in 2001: A Space Odyssey and the short subject Probes in Space. The inside of the Super-Film film magazine was covered in what appeared to be black velvet. The rear surface was a disc spaced from the rear magazine surface to provide a space suitable for 35mm wide film. Thus, when adapted for 35mm film use, the film is offset towards the side of the magazine that opens for loading and unloading of the film. The second magazine type was slightly larger than the Fearless magazine and was obviously designed for 70mm-wide film. The design of the magazine and the mounting style were very similar to those used on 35mm Mitchell cameras. The film chamber had a core 2 inches in diameter, and it appeared that it would hold about 1000 feet of film. We later confirmed that this was indeed a magazine for 70mm wide film and was designed for use on cameras made for the Grandeur format. The third magazine type was an unknown. It seemed to be designed to use 70mm film, and the design and mounting resembled the 35mm designs used by Bell & Howell on their cameras. However, there does not appear to have been any mention in the press of a 70mm Bell & Howell camera being developed. |

|

The Old Large Format Cameras |

|

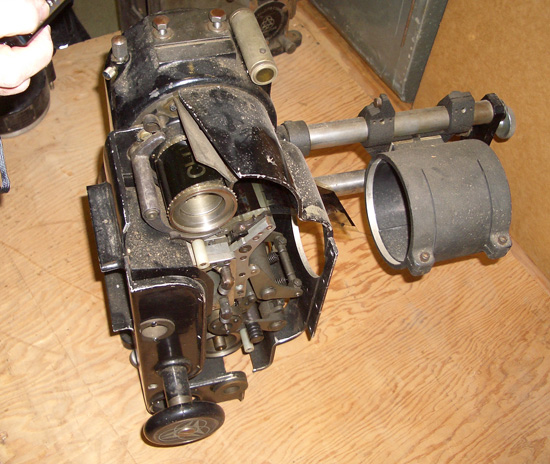

65mm

camera. Image by Dan Sherlock 65mm

camera. Image by Dan SherlockThe first camera examined was truly a strange beast. It was of open construction with no attempt and sound dampening. The overall design, the viewfinder design, and the film magazine mounting technique all seemed to indicate that it was made by Bell & Howell. Since the odd film magazine also appeared to be of the style used by Bell & Howell, we checked and confirmed that the odd magazines fit the strange camera perfectly. No markings were visible on the camera, so there is nothing to prove that it was made by Bell & Howell. But this does seem to be the most likely scenario. The camera had an aperture that measured 0.912 inches tall when measured using a caliper. It was not possible to get the caliper into a position to measure the width directly, but scaling the width from a photo of the aperture reveals that it is about 1.89 inches wide. Although there have been many contradictory specifications given for the Grandeur format, the most reliable information (including measuring several published frame samples) gives the camera aperture dimensions for Grandeur as 1.890 inches by 0.9125 inches. The fact that the camera aperture seems to match these dimensions exactly and the fact that it is designed for 70mm wide film indicates that it was designed for the Grandeur format. |

|

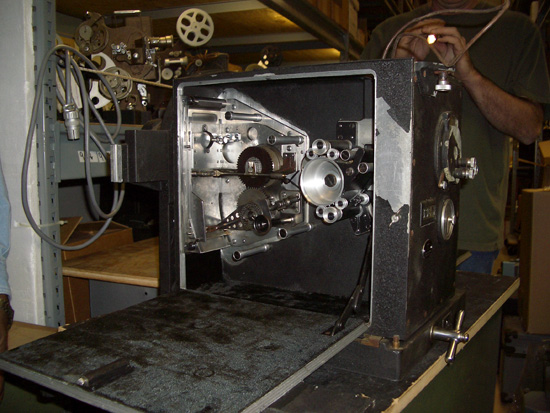

WM.

P. STEIN & CO. nameplate on 70mm camera. Image by Paul Rayton WM.

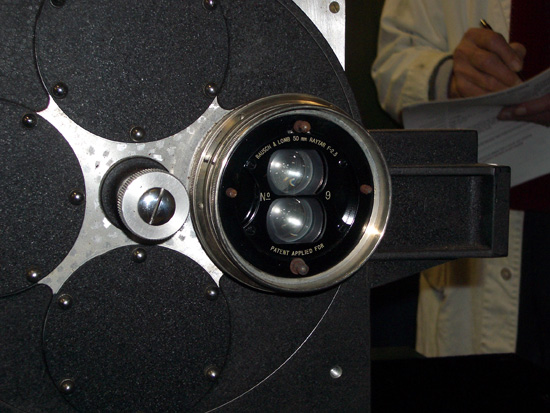

P. STEIN & CO. nameplate on 70mm camera. Image by Paul RaytonThe second camera was one that some of us recognized immediately. It is virtually identical to the camera shown in the photos of the original CinemaScope 55 camera. The CinemaScope 55 camera was stated as having been modified from a Mitchell camera originally made for the Grandeur format. One of these cameras had been on display at the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) clubhouse for several years. However, the nameplate on the camera we examined says "70 MM, [S/N] 9, WM. P. STEIN & CO., NY." and there is no mention of Mitchell anywhere on the camera. (The camera that was at the ASC clubhouse had an identical nameplate but it was marked No. 8.) The design of the camera was very similar to a Mitchell, and the movement was the same style as a Mitchell. And we confirmed that the Mitchell-style 70mm film magazine mounted perfectly onto this camera. But the camera is not the same as the camera made by Mitchell for Grandeur movies. The Mitchell camera was smaller than the Stein camera and looked almost exactly like a conventional Mitchell camera except that it was slightly larger. The gauges and indicators on the back of the camera were also positioned differently on the Mitchell and Stein cameras. |

|

70mm,

dual lens Nature Color, 8 perf Grandeur camera. Image by Dan Sherlock 70mm,

dual lens Nature Color, 8 perf Grandeur camera. Image by Dan SherlockHowever, this camera proved to be the biggest surprise of our visit. For even though it was familiar in appearance, we were surprised to see a dual-element lens mounted to the front of the camera. The lens was marked "Bausch & Lomb 50mm Raytar f/2.3 No. 9". And the case that the camera was kept in was marked "FOX NATURE COLOR FILM – GRANDEUR". Nature Color was a two-color additive process that advanced the film twice the number of perforations that were used for conventional film, to expose an area about equal to two regular frames in size. Nature Color was used by Fox back in the era around 1930, but there was never any indication in what has been published that it was attempted with the Grandeur format. (Apparently the format was originally called "Natural Color", but the name was changed to "Nature Color" around 1930. It is quite possible that the name change was to avoid having a similar name to the competing "Natural Vision" picture format.) But the question remained if it was just a Grandeur camera that had been modified for 35mm Nature Color use, or if it could possibly have been an attempt to adapt the Grandeur format for 70mm Nature Color use. |

|

Upon looking through the viewfinder, we could tell that the image was

deigned to be a widescreen image of about a 2:1 aspect ratio like Grandeur.

When the camera was opened, the mechanism and sprockets confirmed that it

was for the 0.234 inch pitch 70mm Grandeur film and that it advanced the

film 8 perforations at a time, which is the equivalent of two regular

Grandeur frames. But the final confirmation was when we succeeded in racking

over the camera to expose the aperture. There were two apertures, one above

each other, with a strip separating the two. The apertures were measured

with a caliper and were 1.81 x 0.86 inches each. The strip between the two

apertures was 0.080 inches tall, so the total height of the double aperture

was 1.80 inches. Although these apertures were slightly smaller than the

standard Grandeur camera aperture, the aspect ratio is nearly identical. The

viewfinder was aligned so that it would look through the lower lens when the

camera was racked over. Upon looking through the viewfinder, we could tell that the image was

deigned to be a widescreen image of about a 2:1 aspect ratio like Grandeur.

When the camera was opened, the mechanism and sprockets confirmed that it

was for the 0.234 inch pitch 70mm Grandeur film and that it advanced the

film 8 perforations at a time, which is the equivalent of two regular

Grandeur frames. But the final confirmation was when we succeeded in racking

over the camera to expose the aperture. There were two apertures, one above

each other, with a strip separating the two. The apertures were measured

with a caliper and were 1.81 x 0.86 inches each. The strip between the two

apertures was 0.080 inches tall, so the total height of the double aperture

was 1.80 inches. Although these apertures were slightly smaller than the

standard Grandeur camera aperture, the aspect ratio is nearly identical. The

viewfinder was aligned so that it would look through the lower lens when the

camera was racked over.The remaining two cameras were also immediately recognizable. They are nearly identical to the camera shown and described on page 253 of the May 1956 issue of the S.M.P.T.E. Journal. They were painted white, had no viewfinders, and were made by the Mitchell Camera Company and were identified as model "FCD" which apparently stands for "Fox Camera Defense" since they were made for the United States Department of Defense use. The cameras were designed for the 0.234 inch pitch ASA Type I film used by Grandeur. The Mitchell-style magazines that fit onto the Stein Grandeur camera were also confirmed to fit onto these cameras. Since there was no optical soundtrack used, the camera aperture was nearly the entire width between perforations. The camera aperture was square, which gave an aperture size of about 2.25 x 2.25 inches which agrees with the dimensions given in the SMPTE Journal article. |

|

Mitchell

Camera Company, "Fox Camera Defense" 65mm camera made for the United States Department of Defense.

Image by Dan Sherlock Mitchell

Camera Company, "Fox Camera Defense" 65mm camera made for the United States Department of Defense.

Image by Dan SherlockThe only known use of this format for public exhibition of films for entertainment purposes was for the short subject Journey to the Stars which was made for the 1962 World's Fair in Seattle, Washington. The format was called Cinerama 360, and used a circular area about 2.25 inches in diameter with a special 160 degree lens to photograph a wide field-of-view scene for projection onto a large dome screen above the audience. The camera and projector for this film was made by camera division of the Benson-Lehner Corporation (which later became the Cinerama Camera Corporation) and was based on the same specifications as that used by the Mitchell FCD camera. Although the Defense Department appeared to use the 0.234 inch pitch film for many purposes, the use of this film for entertainment purposes and getting it developed by commercial labs proved to be a nightmare. As a result, the second appearance of Cinerama 360 at the New York World's Fair in 1964 used conventional 70mm film, and the ASA Type I 70mm film was never again used for entertainment films. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |