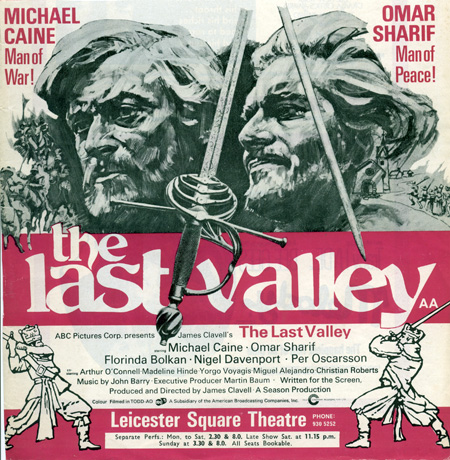

The Last Valley |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Udo Heimansberg, Düsseldorf, Germany | Date: 20.11.2008 |

Udo Heimansberg

introducing "The Last Valley" in Karlsruhe, 2008. Image by Thomas

Hauerslev Udo Heimansberg

introducing "The Last Valley" in Karlsruhe, 2008. Image by Thomas

HauerslevJames Clavell (whose real name was Charles Edmund DuMaresq de Clavelle) was born in Sydney on 10th of October 1924 and died in 1994. It was in 1954, after his time in the army, that he began to write screenplays. These included such classics as “The Fly“ (1958) with Vincent Price, “The Great Escape” (1962) with Steve McQueen, and “King Rat” (1964) with George Segal. His first work as director was the immensely successful “To Sir With Love“ (1967). Besides directing, he also produced this film and wrote its screenplay. He continued to combine all these roles on two more films “Where's Jack“(1969) with Tommy Steele, and, in 1970, “The Last Valley“. However, after the box-office failure of both these latter films he turned to devote himself exclusively to writing: His novels “Shogun“, “Tai-Pan“ and “Noble House“ placed him among the world’s most celebrated authors of best-sellers. His novels were successfully filmed- but now he contented himself with providing the books on which the films were based! “The Last Valley“ was first shown in German cinemas in 1971. Although it had been filmed in 70mm, only 35mm copies (Technicolor print copies!) were used to present it. Ticket sales were abysmal – a fate suffered also, at this time, by many other films of this type. In Germany, the blockbusters of the day were “Easy Rider“, “Woodstock“, “The Graduate“, “M*A*S*H“, and “Catch 22“ along with the works of such New German Cinema directors as Fassbinder, Schloendorff, and the Schamoni brothers. The French Nouvelle Vague and the New British Cinema of the 60’s had also by now acquired an audience in Germany. In this climate, the more intellectual among the film critics tended to display a positively allergic reaction to films made in the “monumental” style – a category which included “Ryan’s Daughter”, “Waterloo”, “Cromwell” and, very decidedly, “The Last Valley”. Neither, however, was this genre of film finding much resonance any longer among the general, non-intellectual cinema-going public. The only successful Cinerama film of the day was Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” – and even this success had looked uncertain at the start. The last two films filmed in Cinerama, however – “Krakatoa” and “Custer of the West” – were unequivocal disasters both commercially and artistically, and their failure served to bury along with them the film format that had been used to make them. ”The Last Valley“ was to remain for many years the last film made in Todd-AO, which fell into a kind of “coma” as a film process after the failure of Clavell’s film. Whereas, however, the decidedly trashy nature of “Krakatoa” and “Custer” had certainly made a key contribution to the demise of the film process used to make them, nothing of the sort could fairly be said of “The Last Valley”. |

More

in 70mm reading: in70mm.com's Todd-AO Page More about Tonhallen Todd-AO Festival, Schauburg, Karlsruhe, Germany Taking a Mini View in a Maxi Way Victor Young |

It has been written of the novelist James Clavell that: It has been written of the novelist James Clavell that:“The real protagonists of his novels are not the human figures who act in them but rather the time and place in which they act. “(Wikipedia) This certainly holds true also of “The Last Valley“. The time is the Thirty Years’ War (1618 – 1648), a war of religion and a complicated manoeuvring for military and political advantage among the European powers of the day. A dark time of denunciations, witch-hunts and epidemic disease. The film begins in 1641, in the 23rd year of the war. The place is an idyllic valley somewhere in Germany, protected from the war by its inaccessibility. A group of mercenary soldiers nonetheless succeeds in making its way into the valley, as does a teacher, Vogel, who had in fact been fleeing from these very soldiers. Vogel thus becomes an intermediary between the valley’s inhabitants – a village community presided over by a man called Gruber and an all-powerful priest – and the captain of a band of mercenaries which is itself no more than an unstable alliance of convenience between adherents to different religious faiths. All resolve to share the secluded valley in peace, so as to survive the winter and the war raging outside. But from the very start, conflict is inevitable. The theme of the film is the two sides of human nature: the longing for peace and the compulsion to violence. Religious fanaticism, a topic still terribly relevant today, dominates even this idyllic valley and the groups unwillingly thrown together in it. |

|

| John Barry, who composed the magnificent music for this film, set parts

of a contemporary poem by Andreas Gryphius (1616 – 1674), which portrays

something of the horrors of this time: Tränen des Vaterlandes, Anno 1636: Wir sind doch nunmehr ganz, ja mehr denn ganz verheeret! Der frechen Völker Schar, die rasende Posaun Das vom Blut fette Schwert, die donnernde Karthaun Hat aller Schweiß, und Fleiß, und Vorrat aufgezehret. Die Türme stehn in Glut, die Kirch' ist umgekehret. Das Rathaus liegt im Graus , die Starken sind zerhaun, Die Jungfern sind geschänd't, und wo wir hin nur schaun Ist Feuer, Pest, und Tod, der Herz und Geist durchfähret. Hier durch die Schanz und Stadt rinnt allzeit frisches Blut. Dreimal sind schon sechs Jahr, als unser Ströme Flut Von Leichen fast verstopft, sich langsam fort gedrungen . Doch schweig ich noch von dem, was ärger als der Tod, Was grimmer denn die Pest, und Glut und Hungersnot, Dass auch der Seelen Schatz so vielen abgezwungen. (Tears of the Fatherland, Anno 1636. Ruined is the land, yes, worse than ruined! Our sweat and all that it has made and earned Is made as naught by sword and cannon, By impudence of swarming foreign feet. Our towers are burning, all our churches toppled, Our strongest slaughtered in the village square. Our maidens ruined , no sight of joy or comfort, Only fire, plague and death where’er we turn. The city streets run daily with fresh blood Three times in six years has the weight of corpses Choked all the streams and rivers Three times have they arduously flowed on. But of the worst I speak not, Of what is worse than plague or fire or hunger: That, ‘gainst their lives, so many have been forced To yield the treasure of their souls’ salvation.) |

|

Schauburg's

poster display for "The Last Valley". Image by Thomas Hauerslev Schauburg's

poster display for "The Last Valley". Image by Thomas HauerslevMany factors make “The Last Valley” an extraordinary cinematic experience: Firstly, the camerawork of Norman Warwick and John Wilcox. Absolutely wonderful use is made of the Todd-AO process. A marvellous contrast is brought out between the interior shots in the narrow little houses and the tiny village church and the exterior takes, with their breathtaking panoramic views of the Tirol’s Gschnitztal. In these latter enormous vistas, the protagonists, whose concerns had seemed just a moment before, in the constricted spaces of their homes and institutions, to be so overridingly important, seem to shrink to mere details in the magnificence of Nature. There are also marvellous shots of the impenetrable surrounding forests, the fields of early-morning mist, the enchanting winter landscapes, which all remain unforgettable. The film, indeed, features none of the “effect shots” typically associated with Todd-AO – no aerial photography or “shooting the rapids” sequences. Clavell always keeps the magnitude of his chosen film format subordinated to the needs of the story he is telling. Secondly, John Barry’s film music. Barry counted at the time as one of the adventurous “Young Turks” of his profession. He had shot to fame through his music for the James Bond movies but was also in demand as a composer among the directors of the New British Cinema. With “The Lion In Winter“ (1968) he had given definitive proof of his ability as a composer of symphonic film music. ”The Last Valley“ counts among the most beautiful and evocative film-scores of his career. Rich in thematic material, full of deeply moving choral sequences (actually sung, moreover, in German!), this score of Barry’s succeeds in bringing out musically the very core and essence of the story told. His monothematically pulsating war themes stand in direct contrast to the romanticism of the music he provides for the scenes of peace. As for Clavell, so for Barry the decisive principle is the objective one: time and place, war and peace. The score features no subjective leitmotifs for the individual protagonists, no “love theme”. |

|

Gschnitztal

today. Image supplied by Herbert Born Gschnitztal

today. Image supplied by Herbert BornThe actors: Michael Caine counts “The Last Valley” as one of his favourites among his films. His role forms a wonderful counterpart to that of Omar Sharif. On the one side, the cold intellectual pragmatist who, like an animal, bends every effort to mere survival, trusts no one and allows no one to draw too close; on the other, the romantic intellectual, the intermediary, the opportunist. At a certain point it becomes clear how similar the two are to one another. They are destroyed by the time into which they were born and in which they became what they are, but they are also transformed by the place they arrive in: the last valley. Per Oscarsson plays the fanatical priest. Is his performance “over the top”? Assuredly it is – but a glance at the religious fanatics of the present day suffices to convince us that “over the top” need not necessarily mean unrealistic. A magnificent performance also from the marvellous Florinda Bolkan, as a woman forced to pay a high price for her independence in a male-dominated society – a highly representative female role, in this respect, in the context of the late 1960’s. The mercenaries too are all convincingly played, Michael Gothard’s performance, in particular, being an incomparable portrayal of viciousness. His character rather recalls that portrayed by Klaus Kinski in “Aguirre, Wrath of God” – although Herzog’s film, in fact, was made some two years later. The locations: the film features very few scenes shot in the studio. The village in which it plays was one built in the Gschnitztal, in the Tirol, between Trins and Gschnitz. Modern houses were hidden by means of camouflage nets borrowed from the German military and the roles of extras were taken on by real inhabitants of the village. The film’s world première was then held in Innsbruck, close to the scenes of its filming. The valley remains still today a place a place of breathtaking natural beauty, although it is by now the site of so much new building that it would be impossible to make there the sort of film that was made there in 1970! Many tourists, however, from all parts of the world are still inspired by “The Last Valley” to visit the Gschnitztal, and the valley’s natives are still happy to relate their anecdotes about the exciting events of the filming! To sum up, then: “The Last Valley” is a film that has all the ingredients of a “monumental” style of cinema which does not, for all that, sacrifice intelligence to monumentality – and which, despite all these virtues, still proved a failure. There are, I believe, only two possible attitudes to this film: either you love it or you hate it - a dilemma curiously correspondent to the dilemma of choice in which the film itself places its protagonists. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 22-01-25 |

|