The Wild Bunch, a modern version of the western genre | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Paulo Roberto P. Elias, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Date: 24.01.2025 |

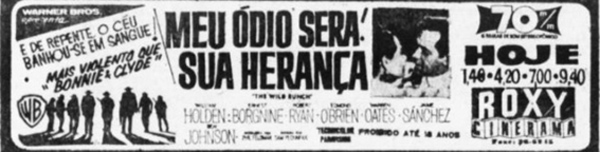

It was approximately July 1970, when the Cinerama screen of the Roxy cinema opened a brand-new exhibition of The Wild Bunch, directed by the “rebel” moviemaker Sam Peckinpah. It was approximately July 1970, when the Cinerama screen of the Roxy cinema opened a brand-new exhibition of The Wild Bunch, directed by the “rebel” moviemaker Sam Peckinpah.The film was shot in Panavision 35 mm and converted to the Cinerama 70 mm format by Warner Brothers. On the screen a new kind of western was featured, showing the reality of the American west. To me, it was the first time ever that bullets were shot and blood spilled off the body of the victim, sort of an ultra-violent depiction of gun fights. However, the film was not about violence, but of a portrait of the actual anachronic western life in the early 1900’s, in high contrast with the situation of the rest of the country elsewhere. In one scene the audience will see an automobile turning up, much to the amazement of the local people, who had never seen one. Those around that new machine claim that it could work on ethanol or gasoline. Also, that a similar machine existed that could fly, i.e., an airplane that was to be used in the war. Yes, at that point in time the world was changing. The automobile would soon replace horses and carriages, and people would be travelling faster than before, in true railroads. But The Wild Bunch focus more deeply on the “Generalíssimo” Mapache, a scoundrel member of the Mexican army, who explores and terrorizes people from the small communities and villages. The General’s army is a gang of soldiers, who helped him to destroy and conquer what he saw fit. To that end Mapache will seek new and more modern armament, with the help of German experts in warfare. Coincidentally, on those days Brazil was under a severe military dictatorship, governed by a hard line General. Censorship was everywhere, on movies, theater plays, books, music, or anything related to a work with an alleged subversion perspective. Artists, journalists and intellectuals were frequently arrested, sometimes subjected to physical torture, or even killed whilst in prison. Nevertheless. Despite the censorship The Wild Bunch was exhibited intact, not a single frame cut by the censors was made. Apparently, they did not notice that the character Mapache is a caricature of the typical military dictator. In other words, it is plausible that the censors did not understand the script’s basic message, or did not get the movie’s main theme, if you will. The term “Generalíssimo” obviously translates to a kind of “top General” so to speak, but, in this case, it is used on purpose, in order to mock and downgrade the power of Mapache. Pike’s Wild Bunch know what Mapache means to that people: terror and intimidation if his wishes are not complied by the local villagers. In the end, Pike and his fellows ask Mapache to retrieve his friend Angelo, but Mapache kills him instead. Pike and his bunch face and fight the General by killing him and most of his army. This is indeed a direct message of the filmmakers to the audience, that they hate dictators and tyrants altogether. It’s a cathartic ending of the Wild Bunch group, which sacrificed themselves for the sake of justice. The Wild Bunch stars excellent veteran actors, namely William Holden, Robert Ryan, Ernest Borgnine, Edmond O’Brien, Warren Oats (last seen in “Blue Thunder”), and Ben Johnson, who was constantly casted in John Ford’s movies. Also noteworthy is the presence of Alfonso Arau in a supporting role, who later directed interesting movies, such as “Walking in the clouds”. Mapache is played by Emilio Fernández, a popular actor in Mexico. Sam Peckinpah, labelled at the time as a “rebel” filmmaker, was clearly an anti-studio system director. His film work demystifies Hollywood’s average Western movies, and avoids the separation of the characters between “good guys” and “bad guys”, in white hats and black hats, respectively. There is no such thing in The Wild Bunch. Peckinpah’s film style has left a legacy on later modern western directors, such as Clint Eastwood, and others with similar stature. Sadly, Hollywood continues to use ultra violence in screenplays, based on computer games, irrespective of the genre, with no meaning at all. Most characters are cartoon-like fictitious. Films such as these are empty, no messages whatsoever! Also, in addition to the violence, the current film style of the camera work and edition are deplorable. Long gone are now the days when the audience would see a real movie, not a streaming BS, made for casual consumers. So much for the Brazilian censors. What they cut in those days is still unbelievable! In Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange feature, for example, they inserted black balls in the actors’ genitals, when Alex and a couple of girls have sex. The balls bounced all over the place, making the audience laugh their hearts out. After the military regime ended so did the censorship. The censors were in fact people working previously as civil servants, mostly policemen, who later returned to their original jobs. Back in the mid 1980’s a young kid used to visit us, on account of computer programming. One day, I got to know that his mom had been working as a censor, and once I had a chance to talk to her over the phone. It was a very interesting conversation, because she did not like to cut other people’s work, and was relieved to stay away from her previous work. At any rate, censorship contributed to the end of a more cultural and civilized time that was undergoing in this country, something that would never be replaced. | More in 70mm reading: Meu Ódio Será Sua Herança, a nova versão do western moderno 70mm Films shown in Brazil in70mm.com News Peripheral Vision, Scopes, Dimensions and Panoramas in70mm.com's Library Presented on the big screen in 7OMM 7OMM and Cinema Across the World Now showing in 70mm in a theatre near you! 70mm Retro - Festivals and Screenings |

• Go to The Wild Bunch, a modern version of the western genre • Go to Meu Ódio Será Sua Herança, a nova versão do western moderno | |

| Go: back - top - news - back issues Updated 24-01-25 |