Some Notes on Shooting "Lawrence of Arabia" | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: © Mike Fox, London | Date: 01.09.2012 |

Towards the end of 1961, I had been a junior

member of DoP Freddie Young’s camera crew for a couple of years. When we

approached the completion of one of my happiest films with him, "The

Greengage Summer", Freddie began talking about our next project: the story of

a British war hero, T E Lawrence, the legendary Lawrence of Arabia. Towards the end of 1961, I had been a junior

member of DoP Freddie Young’s camera crew for a couple of years. When we

approached the completion of one of my happiest films with him, "The

Greengage Summer", Freddie began talking about our next project: the story of

a British war hero, T E Lawrence, the legendary Lawrence of Arabia.I had read The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence’s romantic account of his exploits during the Great War, his famous hit-and-run campaign against the Turkish army in the deserts of Arabia. Among many other books there was even one in particular which claimed that Lawrence was no more than a romanticising bullshine-artist; someone who had grossly exaggerated both the extent and the effect of his contributions to what became known as the Arab Revolt: the allied defeat of Turkey and the subsequent break-up of the Ottoman Turkish Empire. Lawrence was then, and even now remains, a fascinating enigma. But secret papers since released by the government prove beyond doubt that far from being a vainglorious dissembler of the truth, T E and his Arab irregulars contributed far more than Lawrence ever claimed for them in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Moreover, throughout his life he shunned personal publicity like the plague. Thus, by any standards, a major film about such a man was an irresistible project – especially as it was going to be directed by David Lean, a personal hero of mine, who was then riding high on the success of his stunning direction of "The Bridge On the River Kwai". | More in 70mm reading: Restoration of "Lawrence of Arabia" A Message from Freddie A. Young Motion pictures photographed in Super Panavision 70 & Panavision System 65 Internet link: telegoons.org explore.bfi.org.uk |

|

There was only one bugbear: "Lawrence" was going to be made on location,

scheduled to take six months of shooting in the actual locales in the

Jordanian desert. In those days, films could sometimes go a month or three

over schedule – something that is almost unheard of today – as, indeed,

"Lawrence" was destined to do, only more so. As a very young father of two, I

really didn’t want to go away from home for so long; yet I lacked the nerve

to tell Freddie that I wanted out. However, fate had its say. Weeks before

starting, Freddie called me to say that as the film was shooting in Jordan –

the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, a devout Muslim state – Jews were forbidden

from entering that country. As my father was Jewish, Freddie regretted to

tell me that I couldn’t work on the picture. I was suitably dismayed and disgusted by being on the receiving end of such indiscriminate prejudice (an oxymoron if ever there was one), but I guess I must have disguised my relief to Freddie – while welcoming his assurance that despite my absence I would still remain one of his crew. I loved Freddie, who was almost like a father to me. And as much as that I respected him enormously for his work and his utter dedication to it – not as a cinematographer but as an artist. So that was that. Shooting began on "Lawrence" without me – though shares in Columbia Pictures Inc didn’t take a dive because of that – but after many months of shooting, for political reasons, things turned pear-shaped on the shoot. The serious differences that developed between the British production and the Jordanian authorities culminated in producer Sam Spiegel’s complete withdrawal of the unit from Jordan. The production was put on hiatus for a couple of months back in England, while David and production designer John Box and his able crew of location finders went all over Europe looking for a suitable place to continue shooting. That turned out to be the Andalusian town of Almeria in southern Spain and the sand dunes conveniently located just a few miles away on the coast at Cabo de Gata; the highest and most extensive sand dunes in Europe. And again fate spoke up. | |

|

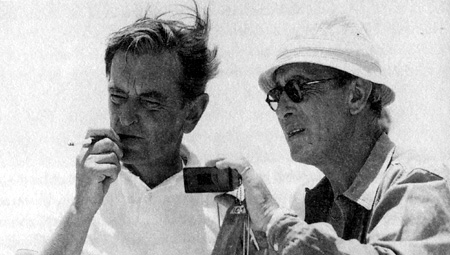

By that time, I had been offered a break from 2AC to 1AC by Nicolas Roeg,

then a nascent DoP who went on to become a talented one and, quickly after,

a cult director renowned for the brilliance of his ground-breaking films. I

was delighted to take the break, though I was very nervous of my new

responsibilities. But having been a 2AC for seven years – a humble

‘clapper-boy’, as we were then called – I had taken much more on board about

the work of a focuspuller than I realised, and handled the job with more

ease than I had ever envisaged. (Be aware, these were the days of

‘rack-over’ Mitchell cameras, ie, cameras where, when running, the operator

was unable to see through the optical system. Using a side-finder he was

thus also unable to see the actual focus detail. That is, not until the next

day’s rushes! Sometimes, for a 1AC, that was a hair raising factor that

caused a lot of sleepless nights.) The "Lawrence" unit had been shooting in Spain for some months when David Lean invited Nico on board to photograph 2nd-unit/2nd-camera directly for him. Peculiarly, this was in tandem to an already existing 2nd-unit already working under the director Noel Howard and photographed by DoP Skeets Kelly; though that unit was completely detached from David. This invitation to Nico was unique because everybody knew that David, being the utter perfectionist he was, had little time for 2nd-units of any description. The rumour was that, left to his own devices, David would have shot every frame of "Lawrence" himself; that it was producer Sam Spiegel’s ‘suggestion’ to employ more units in order to help things along a little schedule (and budget) wise. Be all that as it may, Nico, camera operator Alex Thomson and I were delighted to fly out to Almeria to join the Main-unit for a ‘three or four week’ gig. Ostensibly, our director was André de Toth, a kind of seasoned sub-tyro Hollywood talent whose main claim to fame seemed to be a couple of precociously violent movies and his onetime marriage to Veronica Lake, the once pretty little Forties star with the peek-a-boo hairdo. However, it was only when we broke away from the Main-unit to shoot scripted material that André came into play. There was a reason for this. It was common knowledge that David objected strongly to de Toth’s presence, and de Toth – a burly outspoken personality with an eye patch just like the Hathaway shirts man – was not averse to voicing his odium for David and his much vaunted talents. In the event we stayed for some five months, eventually, sans de Toth, moving with the Main-unit to Ouarzazate, in Morocco, to shoot Lawrence’s murderous attack on the retreating Turkish column. After that, the end of location shooting, the unit wrapped to complete interiors in London’s Shepperton Studios. | |

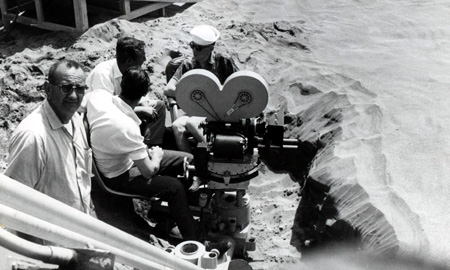

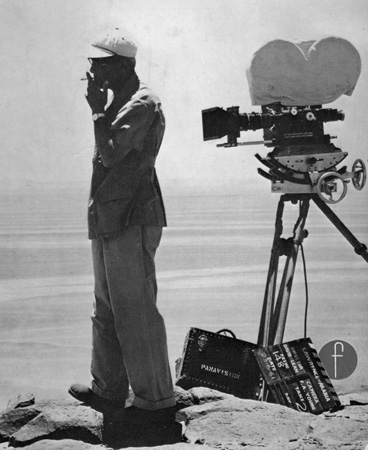

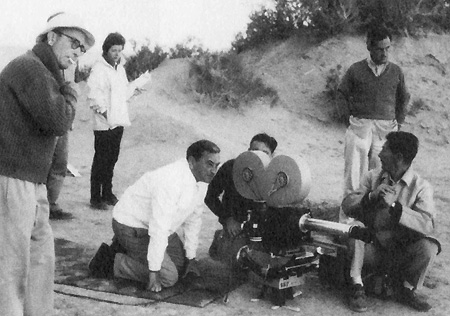

In high summer, Cabo de Gata was roastingly hot; its dunes spectacular,

though the sand particles that formed them were uncharacteristically coarse.

Coarse enough that by mid-morning, when the thermal winds or the occasional

dust devil got them airborne, they chafed our bare skins uncomfortably. They

had other effects. Alarmingly, on checking the gate or reloading – despite

the constant protective cover of thick plastic bags – one would find and

carefully remove a flat teaspoonful of sand from actually inside the camera

body. Yet scratches on the film emulsion were very rare. In fact, checking

the gate or reloading was never done out in the open. The camera was

dismounted and carried into a nearby support caravan to be checked or

reloaded in there with doors and windows tightly closed. In high summer, Cabo de Gata was roastingly hot; its dunes spectacular,

though the sand particles that formed them were uncharacteristically coarse.

Coarse enough that by mid-morning, when the thermal winds or the occasional

dust devil got them airborne, they chafed our bare skins uncomfortably. They

had other effects. Alarmingly, on checking the gate or reloading – despite

the constant protective cover of thick plastic bags – one would find and

carefully remove a flat teaspoonful of sand from actually inside the camera

body. Yet scratches on the film emulsion were very rare. In fact, checking

the gate or reloading was never done out in the open. The camera was

dismounted and carried into a nearby support caravan to be checked or

reloaded in there with doors and windows tightly closed.Design wise, Super Panavision 70 – the appellation for the spherical 65mm system – was then in its infancy. Shooting on Kodak Eastmancolor 5250 65mm neg-stock with release prints on 70mm (magnetic soundtrack area added), there were three types of camera; two of them were based on the industry standard 35mm Mitchells – the soundproof BNC Studio Camera and the unblimped (‘wild’) NC. The 65mm versions, like their 35mm ancestors, were both rack-over cameras, using side-finders for shooting. The third model was the experimental 65mm Hand Held camera, barely comparable to the wild Arri IIc; though, unlike the latter, the ‘HH’ had no mirror shutter and no optical viewing system. The operator both lined-up and shot relying solely on a ‘sportsfinder’ with a matte inserted cut to match the camera lens. (However, if memory serves, one could insert a ground film slide into the gate, and after removing the rear pressure plate, reveal the aperture to view the upside down image. Though this was something devoutly to be avoided with all the sand about.) There was another experimental model, which quickly became Main-unit operator Ernie Day’s camera of choice, whenever sound considerations permitted. This was Panavision’s first Panaflex camera. A hand holdable 65mm reflex model, un-soundproofed, which served to be the prototype for Panavision’s later game changing 35mm reflex model, which was. Looking today at modern film cameras with variable take-up clutches on each magazine, one is fascinated by the simplicity with which those early Mitchell cameras dealt with the problem of taking up the exposed film into the mag’s separate chamber. This was accomplished by no more than a leather friction driven belt running from the main sprocket drive mechanism inside the camera body up to the said chamber’s take-up wheel on the outside of the magazine. On loading the camera, one did no more than tighten any slack in the take-up chamber by hand, then slip the belt on to the take-up wheel to hold the tension there. When running, any slippage caused by a loosened belt decreased the winding action which would create a bowing in the arriving film. As designed, this would quickly knock out the trip inside the camera body. It was foolproof, simple, and it worked excellently – though the belt usually had to be tightened by a camera mechanic from time to time. However, this system led to an astonishing problem on our wild 65mm NC-type camera. One morning, on checking the gate, I opened the camera door to find that the film had completely lost its bottom loop! This was not exactly an unknown phenomenon in those days, when raw stock hadn’t quite reached the heights of perfection that Rochester achieved routinely in later days. But in this case there was a difference: what had been the bottom loop was now virtually straight (which would produce scratching and marked unsteadiness from frame to frame), and there was no visible sprocket damage whatever. In fact, in this condition the camera would run without breaking or tearing the film, which in fact it had. This was impossible! And it caused much scratching of heads between Nico, Alex and myself – the first two having once been distinguished focuspullers of long-standing, whose experienced opinions counted. Of course, as usual, the first instant reaction, lasting only a doubtful second or two, was an assumption that I had laced-up the camera that way. (Puhleese!) We called in our highly experienced camera mechanic, Ted Williams, a British ex-pat who had emigrated to California especially to work for Panavision. He scratched his head too. (Maybe it was a British thing to do. That, or quickly making a cup of tea.) However, after much chat and experimentation, running the camera with waste ends in all kinds of loop configurations, we couldn’t make the camera repeat what it had done. In the end, still perplexed by how the film – its loops locked down by jockey-rollers, themselves held in place by the closed camera door – could jump several sprocket holes without ripping them to pieces and tearing the film to shreds, we had no choice but to conclude that it was a freak phenomenon that most probably would never happen again. Moreover, the labs later reported there was no damage to the original negative. | |

|

But it did happen again! After servicing the camera several times, playing around with the mechanism all night long, Ted finally came up with the answer. The tension created by the leather take-up belt was absolutely crucial. It had to be just right. Too loose, and the exiting film would overrun, bow and knock out the trip. Too tight – with a heavy full load of exposed 65mm film wound on in the take-up side – and the inertia of that heavy mass would impose a force that pulled against the lower jockey-roller and distorted it out of position. Lifted it just enough to allow sprocket holes to escape, one by one, until they were allowed to escape no longer by the loss of the loop itself. Testing this with much lighter waste-ends had not produced the offending inertial force, and that’s why we couldn’t replicate the phenomenon. But Ted found it and cured it, which is why he got the big bucks. Another phenomenon caused some further serious head scratching down the chain of command, from Spiegel, via David, Freddie, the camera assistants, and the labs, and all the way over to Kodak in Rochester. This occurred when the labs made an alarming negative report: the appearance of a thumb print on the neg which repeated itself every 5ft or so throughout the roll. Some genius at the lab forwarded a warning message to us, which went something like: “Please advise camera assistants to avoid touching the emulsion surface when handling the raw stock.” That admonition was too serious to jeer at, but we did conjure up a reply: “Apologies. From now on camera assistants will avoid touching the film while it is running through the camera, especially as opening the camera door would cause total fogging over the scene.” Of course, it was never sent – but two things were certain: the fault was major and the thumb print could not possibly have originated from anyone on the camera crew. The labs cried: “It isn’t us!” and Rochester frowned, “It's unlikely to be us.” A major enquiry began while all our raw stock was checked and/or replaced, and after a week or so the fault was found – in Rochester, in the spooling department, where the uncut major rolls were incised to 65mm/1,000ft lengths and reeled onto their cores. A new employee, set to the work, was helping the strips along by pulling them down, leaving a healthy thumb print on the emulsion as it went along. The guy (or gal) was probably taken out and summarily executed, but the problem was solved. By today’s standards all the 65mm cameras were very heavy – particularly the blimped Studio (BNC-type) model, which, without exaggeration, took four men to carry and mount; the front end considerably heavier than the back end. I would guess that the camera with a 1,000ft of 65mm film in place weighed at least 100lb. To cope with it, Ernie used the slightly elongated Mitchell geared head, the beautifully designed and robustly engineered version originally adapted for use with Paramount’s not quite so heavy VistaVision ‘Lazy-Eight’ (35mm horizontal exposure) system. It performed admirably. The 24v Super Panavision batteries were very heavy too, and an even heavier one was always carried to plug into the camera body to keep the film gate within its crucial design tolerance at the film plane by maintaining a constant temperature of 80˚f. The weight factors were made even worse by the Panatron start box. It ran the camera at precisely 24fps (at a rate of 112.5ft per minute, per the 5-sprocket 65mm frame area compared to that of the 4-sprocket 35mm standard). The Panatron was superb but it must have weighed at least 30lb. So, what with the sometimes debilitating heat, the energy sapping sand dunes, and the excessive weight and profusion of our necessary camera gear, moving from setup to setup with 65mm could never be described as hit-and-run shooting. There were other minor but taxing problems for a 1AC. In 65, the gelatine filter slides mounted in the camera gate – usually a Wratten 85 or combined 85+.3ND or 85+.6ND – had to be kept spotlessly clean. Even a fine speck – given a T16, or more, lens aperture – could be rendered focused enough to be visible on the prints. (A lesson instantly learned.) And as you would expect, 65mm lenses’ focal lengths were drastically increased over their 35mm counterparts. Again if memory serves, our ‘wide angle’ was a 50mm. Often, for close-ups, we’d use a 210mm. This posed little problem in daylight shooting at small lens aperture settings, often between T11-T16. But on night shooting, it was a different story. A 210mm close-up, the lens wide open at probably T4, could overwork one’s sphincter muscle more dramatically than anything going on in frame. (At least, it did for me.) | |

While talking of filters, a note on how Freddie photographed the wonderful

moonlight scenes on Lawrence’s poetic desert exteriors. Once-upon-a-time,

there were two of a standard range of filters used in black-and-white

cinematography: the 3N5 and the 5N5. These were made up of a light yellow

Aero1 and a heavier version Aero2, each combined with a 50% neutral density.

Using them, the exposure compensations were (I think) respectively 1.5 and 2

stops. Employed mainly to increase contrast while darkening blue skies and

whitening fluffy clouds, they were most often mounted to reproduce a

moonlight effect in day-for-night shooting. Usually this was done in strong

backlight with DoPs adding whatever amount of fill-light to the foreground

action as taste or technics were thought necessary. While talking of filters, a note on how Freddie photographed the wonderful

moonlight scenes on Lawrence’s poetic desert exteriors. Once-upon-a-time,

there were two of a standard range of filters used in black-and-white

cinematography: the 3N5 and the 5N5. These were made up of a light yellow

Aero1 and a heavier version Aero2, each combined with a 50% neutral density.

Using them, the exposure compensations were (I think) respectively 1.5 and 2

stops. Employed mainly to increase contrast while darkening blue skies and

whitening fluffy clouds, they were most often mounted to reproduce a

moonlight effect in day-for-night shooting. Usually this was done in strong

backlight with DoPs adding whatever amount of fill-light to the foreground

action as taste or technics were thought necessary.Freddie used these B&W filters, without compensating the exposure, to do the same thing in colour. However, every time he did this, we were to instruct the labs on each neg-report in large letters: “DAY-FOR-NIGHT: PLEASE ADD FIVE POINTS OF BLUE.” The rushes were stunning – and, of course, Freddie received a well deserved Oscar for his magnificent work. That is not to overstate: no less than a half-century later, "Lawrence of Arabia" is still regarded as the finest example of desert cinematography ever photographed in the history of feature filmmaking. I can’t think what a talented DoP today would have to do to beat it or even match it. You might ask why? Because you’d need to find a master director like David Lean to give the time and encouragement to his master DoP to do what Freddie did. Plus you need gifted screenwriters like Michael Wilson and Robert Bolt to write unforgettable dialogue to set it all against and, further, to counterpoint it with a wonderful music track composed by Maurice Jarre. No less, you’d need a master producer like Sam Spiegel, with the clout and the tolerance to schedule and budget for excellence in the way he did. And such a group of maestros would be extremely hard to find and put together in these days of the beancounter and CGI and computerised thinking. I believe "Lawrence of Arabia" was unique. Both the first and the last example of a major supremely successful feature film made where excellence had completely transcended expense. Though I never laid eyes on it, the original shooting schedule for "Lawrence" was widely accepted as being six months. In the event, that stretched to somewhere near 14 months! But the finished product – outstanding in every area of cinematic art and craft – enshrined its creators’ names in film history for all time. | |

Post Script | |

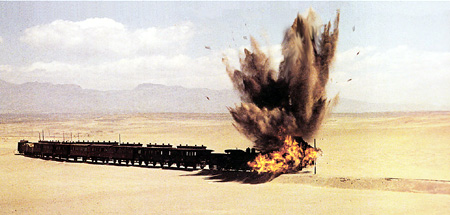

For all the praise heaped upon

"Lawrence of Arabia" by academies and critics,

associations and film-buffs, from all over the world, there was one

miniscule virtually unnoticeable flaw in the picture. A flaw known to

probably only three people out of the tens of millions of those who have

seen the film: Nicolas Roeg, Alex Thomson, now sadly deceased, and me. For all the praise heaped upon

"Lawrence of Arabia" by academies and critics,

associations and film-buffs, from all over the world, there was one

miniscule virtually unnoticeable flaw in the picture. A flaw known to

probably only three people out of the tens of millions of those who have

seen the film: Nicolas Roeg, Alex Thomson, now sadly deceased, and me.It occurs during a majestic shot, which David Lean had given to Nico’s crew, my crew, to shoot. Set up on top of a high dune at Cabo de Gata, looking down through the blazing sun at the desert below, a Turkish train snakes along at speed on its way to being blown off its rails by a team of special effects men. As the train progressed across frame, I heard “Fuck!”, quickly followed by a ‘click’, as Alex hurriedly flicked off the pan-lock on his geared head. He had accidentally left it on after David had climbed all the way up the dune to check the composition of our shot. (He had loved it.) The effect of that little click is in the picture and I’ve seen it dozens of times in countless screened excerpts about the movie, not to mention in the movie itself. The train progresses just a whisker too far across the huge 70mm frame, then there’s the tiniest jiggle on-screen, after which the camera begins to pan smoothly to capture the huge explosion and the train flying off the rails. You’ve seen it too, dozens of times and never noticed it. It always makes me laugh – as it did Alex, but much later... | |

Important Notice | |

As a relatively junior member of the camera crew I was never privy to the

machinations among the top brass that collaborated, cajoled or conspired to

create one of the greatest movies of all time. But working alongside so many

of my heroes – truly among the cream of the British film industry’s very

best – I was wise enough to keep my eyes and ears wide open. This, because

it didn’t take long to realise that we were all working on something that

was going to be very good, if not uniquely great. As a relatively junior member of the camera crew I was never privy to the

machinations among the top brass that collaborated, cajoled or conspired to

create one of the greatest movies of all time. But working alongside so many

of my heroes – truly among the cream of the British film industry’s very

best – I was wise enough to keep my eyes and ears wide open. This, because

it didn’t take long to realise that we were all working on something that

was going to be very good, if not uniquely great.What we didn’t know was that such assumptions were a serious underestimation of what "Lawrence of Arabia" was to become and the reverence in which it would always be held. I had worked on many large films led by many directors of varying talents, but never one so consummately gifted as David Lean. One treasured memory that brought this home to me at the time was the famous sequence of the attack on the Turkish train. I always managed – without getting in the way – to get as close to the echelon that formed around David whenever he lined up a shot: himself at the head, 1AD Roy Stevens on his right, Freddie and Ernie on his left, script supervisor Barbara Cole and Props Czar (there is no other word) Eddie Fowlie no more than a couple of paces away – and me, my straining ears like a pair of riding-boots strapped to the side of my head. It was the beginning of the sequence when Peter O’Toole, in his Arab dress, climbs to the roof of the train to strut along its top, exulting in the complete success of the attack – just before he is wounded by a shot from a dying Turkish officer. David was quietly agonising on how to begin shooting it and, as was his won’t, was taking forever to make up his mind. He either listened in silence or fended off any guardedly presented suggestions from his trusted crew. And during this I heard him say: “This has got to be special. This is where I’m going to bring up the music, the main theme of the film...” And that is exactly what happens in the finished film. What was impressive? At that moment, Maurice Jarre had not then even been approached let alone commissioned to compose the magical theme that he did; and I had never before witnessed a director’s clear uncluttered vision of what it was he intended to do, was intent on doing – and did. But please be warned, there are many details in these notes that I have had to rely on from memory alone: events, incidents and factors that prevailed fifty years ago. Bearing that in mind, it could be that here or there I have mis-remembered something. The batteries for the 65mm cameras, for instance, may have been 110v-packs rather than the 24v mentioned. The wide angle lens might have been a 40mm rather than a 50mm, and so on. But what I can testify to is that the generality of the facts and figures and the other detail, while perhaps not being too scholarly or absolutely precise, are most certainly within the ballpark. Thus, if you do find an error, I crave your indulgence... | |

Footnotes by Mr. Christian Appelt | |

|

Using a side-finder he was thus also unable to see the actual focus detail.

That is, not until the next day’s rushes! 1) When the shooting day is over, all rolls of exposed camera negative are processed and printed to positive film stock. This work usually is done overnight so the director of photography and director can watch the results the next day. The British call these viewing prints rushes, in the United States they are called dailies. ******************* It was common knowledge that David objected strongly to de Toth’s presence, and de Toth – a burly outspoken personality with an eye patch just like the Hathaway shirts man 2) In 1951, the "Hathaway man" who sported an eye patch was created by advertising agency Ogilvy & Mather in their famous campaign for men's shirts by C. F. Hathaway. André de Toth lost an eye in an accident when he was a young man, which did not prevent him from directing successful 3-D movies like House of Wax (1952). ******************* Yet scratches on the film emulsion were very rare. In fact, checking the gate or reloading was never done out in the open. 3) The film gate guides the film stock at the point of exposure. During production, the gate is checked periodically to make sure that neither dust, hair or other debris have accumulated in the gate because they would be visible in the finished shot, usually at the top of the frame. A gate check (and cleaning, if necessary) can be done by removing the lens or by opening the camera and pressure plate. ******************* Design wise, Super Panavision 65 – the appellation for the spherical 65mm system – was then in its infancy. Shooting on Kodak Eastmancolor 5250 65mm neg-stock with release prints on 70mm... 4) Like the original Todd-AO process, Super Panavision used non-anamorphic lenses and 5-perf 65mm film stock and had an aspect ratio of 2.21:1. In following years, it was also referred to as Super Panavision 70 and Panavision 70 (which also designates blow up versions of 35mm anamorphic negatives to 70mm release prints, propably to create confusion among film format buffs). ******************* The 65mm versions, like their 35mm ancestors, were both rack-over cameras, using side-finders for shooting. 5) The Mitchell camera's body (taking mechanism and film magazines) was mounted on a sliding base plate behind the lens mount. To set up shots, one "racked over" the camera body to bring a ground glass and viewing system behind the taking lens. Then, the body was moved back to position the film gate in its proper place behind the lens. During shooting, an auxillary side viewfinder was used, which did not show exactly the same perspective, and the assistant had no way of confirming whether his focus pulling was correct - until the next day's rushes. ******************** However, this system led to an astonishing problem on our wild 65mm NC-type camera. One morning, on checking the gate, I opened the camera door to find that the film had completely lost its bottom loop! 6) The film stock runs through the camera in continuous motion, except for the film gate where it has to stand still during exposure. To prevent the film from ripping, it is formed into a loop above and one below the film gate to compensate for the change from continuous to intermittent motion. If loops are lost, this may result in sprocket damage and unsteadiness, rendering the footage unusable. ******************** There were other minor but taxing problems for a 1AC. In 65, the gelatine filter slides mounted in the camera gate – usually a Wratten 85 or combined 85+.3ND or 85+.6ND – had to be kept spotlessly clean. 7) A Wratten 85 color correction filter was necessary for daylight shooting since Eastman color negative at that time was sensitized for artificial (Tungsten) lighting. - ND (neutral density) filters are tinted grey to reduce brightness without stopping down the camera lens too much. | |

| Go: back - top -

back issues -

news index Updated 22-01-25 |