When Work is the Ultimate Play?! | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Mark Lyndon. Friday 26 November 2010. Retyped from audio files by Margaret Weedon. Thanks to Christian Appelt for proofreading | Date: 06.12.2010 |

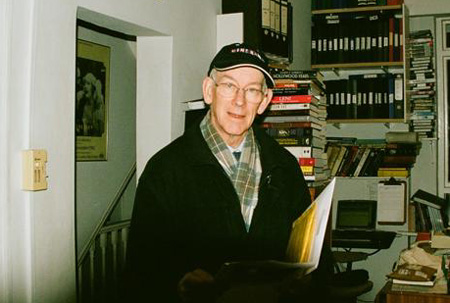

Kevin

Brownlow in his home November 2010. Image by Mark Lyndon Kevin

Brownlow in his home November 2010. Image by Mark Lyndon ML: The novelist J.G. Ballard once foresaw an age in which work is the ultimate play and play the ultimate work. Most of us have not been fortunate enough to have reached that happy condition. However, In70mm.com has been fortunate enough to have been granted an interview with Kevin Brownlow – author, auteur, film historian, the world authority on silent film, and Greta Garbo and now the recipient of the ultimate award – the Oscar - in recognition of a life time of work, or was it play? KB: There is nothing like spending your life doing what you want to do – but the curious thing is the more you do that the more responsibility creeps up on you and actually you find in the end that play becomes very serious work; on the other hand you would not have it any other way. ML: How serious can it get? For instance the picture of you on the website for the Oscars showed you standing next to a certain gentlemen with a beard. KB: This is something like a side line - award ceremonies and such things, I think that the law suit is now passed – it has been settled out of court and we are hoping that we can all work together. • Go to The Cinerama Archaeologists • Go to Die Cinerama-Archäologen • Go to Theo Gluck and the Interest in Movies - A Master Class in Film Restoration | More in 70mm reading: Kevin Brownlow visits the Schauburg in Karlsruhe Kevin Brownlow Interview - Part 2 Projecting “Napoleon” – une pièce de resistance Carl Davis Interview The Cinema Museum, London Robert A. Harris: Film Restoration on the eve of the Millennium A View from the Trenches |

Kevin

Brownlow lecturing about silent movies during the Berlin Film Festival "Berlinale

2009". Image by Thomas Hauerslev Kevin

Brownlow lecturing about silent movies during the Berlin Film Festival "Berlinale

2009". Image by Thomas HauerslevML: So there is a definite possibility of a performance of the greatest film ever made – if I may call it such? KB: Absolutely, yes, we hope there is. ML: The Festival Hall, or the Barbican or would it be in America – have there been any indications? KB: We do not know yet because there is an awful lot of digital work that needs to be done. ML: In other words, there has been a rapprochement between all parties. KB: Yes, well the idea is that the Coppola version will be upgraded with our material and eventually we hope that our version will be on DVD. ML: On Bluray ? KB: Yes. ML: Hopefully this will be with the Carl Davies score. Has there been a compromise with the Carmine Coppola score? KB: No! That will always be on their version. ML: But they have given permission to release both versions? KB: I think that the idea is that both versions will be available but, God, it is taking a long time. | |

The Discovery | |

|

ML: I wanted to talk a little bit about

the film itself: the discovery of the film, the amazing circumstances –

some might say there might be a biopic in it at the end of this long

journey, which started in 1954, a watershed year, a

Todd-AO feature had started

production, with "Oklahoma!", Cinerama had crossed the Atlantic,

Abel Gance had crossed the channel to see

Cinerama in Old Compton

Street, and the two of you met in the BFI offices at that time, which

were in Shaftesbury Avenue. Thomas

mentions that you had

many amusing anecdotes about this encounter and the consequences. KB: You need to go back a little bit because I met a journalist called Dr Francis Koval and he had lent me a photograph of Gance, which Gance had signed to him and this was my first year of professional writing for a little magazine called “Amateur Cineworld” and that December they were doing a piece in which Napoleon appeared. I sent them this photograph of Gance and the printers very obligingly used acid to remove the signature at the bottom of the picture. I could not believe it! – I was intensely embarrassed about this, and had to hang on to the photograph until I met Gance again to get him to re-sign the photograph. | |

“EST VOUS MONSIEUR GANCE ?” | |

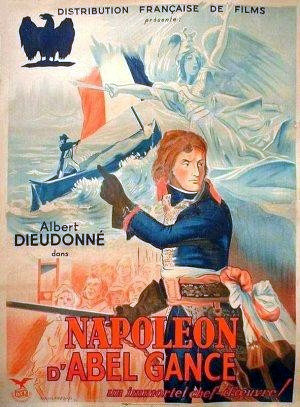

Maybe

a Dutch "Napoleon" poster, seen on the internet Maybe

a Dutch "Napoleon" poster, seen on the internetBut what happened was I showed it to my friend Liam O’Leary who was the deputy curator of the National Film Archive, and a few days later he was in his office at the BFI and he looked through the glass door and he saw the man in that photograph: so he went out and in his execrable Irish accented French he said “Est vous Monsieur Gance?” – and Gance was staggered to be recognised; Liam went into James Quinn, who ran the BFI in those days, and he authorised a reception at the then new National Film Theatre. Meanwhile, cut to me; I was hard at work on a mock school certificate exam in German and the only way you could ever get out of something like that was if there was a death in the family – and when a telephone call came through to the school they automatically assumed there was a death in the family, and let me go without ever asking me any question at all. My mother said come home straight away – and go home I did - and she said Abel Gance is at the NFT – he has just been in touch. So I grabbed the script, which had been published in French, and the few stills I had and rushed off to the NFT. There I met the great man. I remember the taxi arrived and this remarkably handsome individual got out with his hair swept back like a medieval saint, with a beatific smile, and of course I cursed the hours I spent studying French but not really paying attention; he did not speak English so we had a problem there but, luckily, there were enough people to translate. | |

Kick-start the Restoration! | |

|

By that point I had most of the film on home movie – quite the opposite

of your wide screen – I had it on 9.5mm; the more I got of it the better

it got until the end - and I could not understand why we had endless

shots of troops marching left to right and right to left – they had

deconstructed the triptychs and put them one after the other. Anyway,

that was the beginning of my complete obsession with this picture and

when I got into the film industry I was able to make a documentary for

the BBC about Gance and find footage that had been missing from the film

since its original release and that is what kick started the

restoration. ML: This was something of a grail quest – hence its suitability for a biopic eventually - but did you ever despair? KB: No! ML: At which point does a hobby become an historical mission – let us put it this way – did you realise how important this was ? KB: No! First of all you have to remember there was a tremendous prejudice against silent films in that period – the WW2 generation completely rejected them, and they always said oh you must be joking, these films are jerky, flickery and ludicrously badly acted, and I could not understand this. ML: The ignorance was stunning - who was to blame? KB: This was partly due to the fact that distributors used to put out films made about 1912 at 16 frames a second shown at the sound speed of 24, so everything looked ridiculous to start with. They put on honky-tonk music and Keith Smith type commentaries and people just fell about, and the older people thought “Was this what we fell in love with all those years ago?” - and they were embarrassed to talk about silent films because they looked like that... KB: Thus, the technicians of the past were regarded as idiots, and I have always felt it was my crusade to show actually it was not quite true; they were so brilliant some of them that we have not quite caught up yet. Everything - and this took me a long time to realise, but every visual advance in the cinema, except for obviously CGI, occurred in the silent era. | |

The Chase! | |

Poster

from the internet Poster

from the internetKB: I knew that the film had been released on 9.5[mm] in six reels, and I advertised in Exchange and Mart, and I tramped around London; went to every film library, and eventually got all six reels; historians used to come to see it at my flat – David Robinson, Derek Hill, Lindsay Anderson, it was really thrilling. I had orchestral accompaniment on turntables, and great overuse of the 1812 [overture], but that picture, even in that form, was absolutely thrilling. I felt it was the cinema as I thought it ought to be – not simply was the 18th century recreated incredibly accurately, it looked like a newsreel of the time, but the camera did things I had never seen it do. For instance, there is an astounding sequence of a storm in which Napoleon is caught in a storm off Corsica in an open boat. This actually happened and Gance discovered that at that same night in the Convention there was a riot in which the Jacobins turned on the Girondins - the extremists turned on the moderates, and he wanted to recreate the line of Victor Hugo – “to be a member of the Convention is to be a wave on the ocean”. KB: He told this to his technical director, and the technical director rigged up a trapeze on which was a camera, and it hurtled down to the crowd, giving the impression of a wave. Anyway, I looked at this as a kid and thought “This is it!”. I had never seen anything like this – you never see anything like this in the 1950s Odeon, I can tell you – everything was long and thin - people lined up to deliver their lines and we got films like “The Robe“ (I did not see that film, so I must not be cruel about it.) ML: Burton was being neurotic basically. | |

The Long way around it | |

|

The Long way around it KB: I found those early CinemaScope films extremely fuzzy and extremely dull and here was the same idea but done with such enthusiasm and excitement. So I wrote a fan letter to Gance and he replied to it – and that was the very, very beginning of my contact with him, but after that I stayed in contact; went to Paris, met him and then began the restoration which took 25 years – obviously not doing it all the time, but in order to find the material I had to have some sort of contact with the Archive Movement and that did not happen until I had started. I had to use my own money for all this, and a friendly fellow at the BFI allowed me a viewing room at the BFI and the Head of the Archives did not approve of me because I was a film collector - so it was like the old barometers – he came out of one door and I went in the other door. ML: Like a Feydeau farce? KB: Yes, and I had all night to work on the picture in this viewing room; I had twelve weeks of nights putting this together. The man who ran the central booking agency - David Meeker – he told Jacques Ledoux, who was head of FIAF (International Federation Film Archives) and he took it upon himself to contact all the archives saying if you have anything on "Napoleon" send it to Kevin Brownlow at the BFI. And by God, the cans came in like this – many rusty, the films like cellotape, but much of it was in perfect condition – as I recall it – and I may be exaggerating – every single reel had something new which was not in the 9.5[mm version]. |

|

AN AVANT GARDE RETROSPECTIVE! | |

KB:

Also - and this is very important - in 1965 the BFI put on an avant

garde retrospective and "Napoleon" was shown for the first time

since its release, and the Cinémathèque Française sent their “not very

good print” – “not very good” - it was a catastrophe! KB:

Also - and this is very important - in 1965 the BFI put on an avant

garde retrospective and "Napoleon" was shown for the first time

since its release, and the Cinémathèque Française sent their “not very

good print” – “not very good” - it was a catastrophe!ML Was this [Henri] Langlois’ fault basically? KB: Yes! - Luckily I could recognise it – if I had not seen the 9.5[mm], and I had only seen that, I would have walked out of the cinema and never had anything to do with the film again. In fact I did walk out – I took my then girl friend trying to impress her – and it was so awful we had to walk out. It had tests in it - for instance – a close up of Albert Dieudonné – he was doing this - (strikes a ludicrously theatrical pose) - for about five minutes! ML: Like an early Portillo impression?! KB: Yes, the audience was falling about! But what happened was sixteen other images were to be superimposed over this and it worked superbly in the film but Gance wanted to see what it was like without anything and was testing it; and Langlois or someone dropped it into the film and that sort of thing was unforgivable , and so I have no regrets that when they sent their good print – tinted – incomplete – but a good print – I borrowed it and copied it ; and it was just as well because it was eventually destroyed in one of the Cinémathèque’s fires and that copy became the basis for THE BIG RESTORATION. When I did that - 12 weeks of nights - that was the print I worked on – and again, I paid for that, so nobody was losing money except me. |

|

“NAPOLEON” | |

|

“NAPOLEON” KB: Occasionally we showed it at the NFT to show progress, and [get] the reaction of the audience – it was always jammed, and people would write afterwards to say how incredible it was – and I would send these letters on to Gance. He became so excited himself he made another version, which was not a good idea, because it was a documentary rather than what he had originally filmed. Anyway, the fact that he was working on it allowed me to have access to his negatives as well – he managed to get it out of the Cinémathèque: this could go on forever – I must stop it. | |

The Technical Aspects? | |

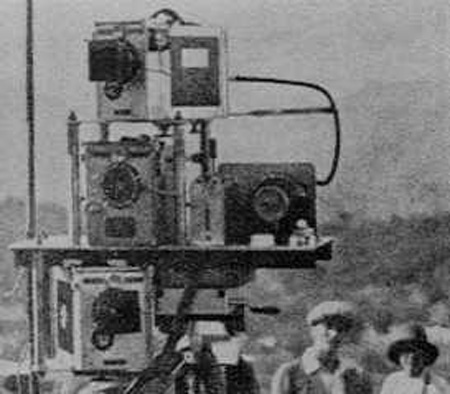

Polyvision

camera set-up. Note the cameras are on top of each other. Polyvision

camera set-up. Note the cameras are on top of each other.ML: I am curious - as indeed are our readers - about the technical aspects which still are in many ways ahead . KB: There is a wonderful man called George Dunning – who [was] an animator responsible for “Yellow Submarine”, and he had the idea with Richard Arnell of putting on a Wide Screen Festival at the Odeon Leicester Square. I had nothing to do with this, but he was bright enough to contact [Henri] Langlois and borrow the triptych. I don’t know at what point I was told about this, but I remember going in to the Odeon Leicester Square and seeing the projectionists with sledge hammers hitting the projectors so that the three projectors they had would line up more closely together; they still had unfortunately a black line between the pictures but they did present the triptych – they were running original nitrate. I do not think they realised that – and of course my eyes lit up – I filmed it off the screen and I remember the audience consisted of the makers of commercials. This was in the middle of the day that it was presented – and I remember people who found it difficult to make a 30 second commercial, tittering at Gance’s triptych! KB: I went to see George Dunning – he was Canadian - hoping obviously to get my hands on this – and he said “I have got bad news for you, Kevin – I sent it back” – long pause – “but I copied it first and I think you ought to look after it!” So he gave me 35mm negatives of the triptychs from "Napoleon" – so that was a pretty good start. ML: You were really the single point of contact, for this project that was taking a life of its own; were they beginning to realise just how big this mission was? KB: No! ML:...and that you were God’s representative on earth, or Gance at any rate? | |

“Long thin pieces of ripped film !” | |

|

KB: It really was something that was occasionally shown at the NFT -

full stop! I remember being very hard on Langlois - having stolen his

print – got it into the lab - it was in a shocking condition. There were

bits of film hanging off like confetti – I remember going on the stage

at the NFT and demonstrating these long thin pieces of ripped film to

the audience, but nevertheless it produced a very good image and in 1979

– or a bit before that - President Nixon banned a film that was going to

open the American Film Institute Theatre in Washington – called “State

of Siege” – by Costa-Gavras. So David Shephard who was the archivist at

the AFI, and a friend of mine, said I have got permission to install

triptych projectors to the AFI theatre in Washington, why don’t we

launch it with "Napoleon", and this was agreed. | |

THE RIGHTS | |

|

KB: I had no rights, as Patrick upstairs keeps reminding me, had I

acquired the rights none of the problems we are having now could have

occurred, but I never thought that anything would happen with this – I

was still that kid with the 9.5[mm] projector. So it was a fantastic; I

was not there, but I heard it was an incredible success – a standing

ovation; then in 1979 the organisers of the Telluride Film Festival rang

up and said – “Do you think Gance would come to Telluride?” – I said -

“I am afraid not, he has been very ill, he is 89, there is absolutely no

chance at all”. Well, it is a horrible journey to Telluride – it takes

about 24 hours - and when I finally got there, reeling from the

experience, there was Gance! - He was expecting to see "Napoleon"

complete, and there was a tribute to him in the Opera House; I was asked

to show my documentary about Gance – well fine, he has seen it – it is

not a surprise – and he liked it, he approved of it, but he did not

approve of it this time! I was to give him his Telluride medal – he went

on the stage and he said in French to the audience – which was

immediately beautifully translated – “don’t judge my work by the rubbish

that you have just seen – these pieces of poem have been put together

..* !..” – Then I had to put the medal on him – I wanted to strangle

him!! | |

AN ICE COLD NIGHT! – BUT COPPOLA SAW IT | |

KB: He thought that this was the restoration. He did not realise that he

was going to have to suffer through an ice cold night from 10 o’clock

until 3 o’clock the next morning watching it outside because it needed a

huge screen – and he had retreated to his hotel room anyway which was

behind – but then he realised and apologised - and that was when Coppola

saw it and thought “My father keeps telling me that silent films had

orchestras, let’s put a symphonic orchestra with this” and I did not

think anything would come of it, but indeed it did – and Coppola Senior

came over to London to meet Carl Davis, who had just finished a 13 hour

series that David Gill and I had made called “Hollywood” – which is the

history of the silent film in America. Carl had left - gone to America

to meet the surviving musicians. KB: He thought that this was the restoration. He did not realise that he

was going to have to suffer through an ice cold night from 10 o’clock

until 3 o’clock the next morning watching it outside because it needed a

huge screen – and he had retreated to his hotel room anyway which was

behind – but then he realised and apologised - and that was when Coppola

saw it and thought “My father keeps telling me that silent films had

orchestras, let’s put a symphonic orchestra with this” and I did not

think anything would come of it, but indeed it did – and Coppola Senior

came over to London to meet Carl Davis, who had just finished a 13 hour

series that David Gill and I had made called “Hollywood” – which is the

history of the silent film in America. Carl had left - gone to America

to meet the surviving musicians.KB: Anyway at the end of “Hollywood”, David and Carl thought it would be wonderful to put these pictures back in the theatre with orchestras – orchestras make all the difference – OK, you could see silent films with good pianists, and it is very effective, but nothing matches the orchestra and they suggested “Broken Blossoms of Griffith” with Lillian Gish; and in order to get permission they showed it to a Thames TV producer whose reaction was “too corny”: so then David said, what about "Napoleon" – and I said “Oh come on – it is practically five hours, you would never get an audience sitting for that long”. But let’s see it – and they saw it - and they saw it on a Steenbeck [editing table]. I do not think either of them were 100 per cent, but they went with it, and Carl had three months to write the score. | |

Something really unusual | |

KB: I was petrified, I thought this was going to be the end of my love

affair with "Napoleon", and when I came out of the tube station that

Sunday morning there were people sleeping out on the street to get

tickets for this, (and that was before Mrs Thatcher made it statutory),

it was jam-packed, and I knew that we had something really unusual. A Polyvision scene from "Napoleon". A triptych panorama of three frames

side-by-side A Polyvision scene from "Napoleon". A triptych panorama of three frames

side-by-side At the end of the second reel, which is a very moving episode in which the young boy as a cadet is turned out of school, after a pillow fight, which is shot in Polyvision, of nine, six, twelve, images all at once – he is thrown out into the snow, and his eagle, which is being let go by the other kids, comes back to him on the canon, and Carl’s music for that was just devastating, and to the audience it was incredible. ML: The emotional impact of that was the greatest I can recall - having Carl with the live London Philharmonic – and the war child; he sleeps on the canon, it was so powerful – visceral, really. KB: Yes - absolutely! Then I realised that we had a hit. Jeremy Isaacs who had started the Hollywood series (he was going to run channel 4) came out of the cinema and I heard him saying if this is not on channel 4 there will not be a Channel 4. So people came up afterwards and said ”It has changed my life”. ML: A life changing experience. KB: Yes - and it has been like that with every screening. | |

AND SO - TO NEW YORK! | |

Polyvision

scene printed on 70mm film for 1980s release Polyvision

scene printed on 70mm film for 1980s releaseKB: Well, now we have to go to New York and now the Americans have decided that – and this is legitimate – they were going to cut the film because they wanted to put it on at Radio City, which was a very brave thing to do, and they needed to cut it down because the slot was four hours, I think, so I said that Gance had had exactly this experience at the Opera in 1927, and he cut it down to three and a half hours; so they followed the same cutting order but what they never did was to put it back and show the restoration complete, or as complete as we could in those days. However, I was there this time - it was introduced by Gene Kelly – Lillian Gish was there, Leonard Bernstein – the whole of New York show business set was there; taxi drivers were talking about it - 6,000 people a night – they had to keep extending it, it was such a smash, but I noticed that the music, although it consisted of some fine pieces by Mendelssohn and so on, it did not have the same effect that you and I experienced with Carl Davis. ML: Davis is a genius, quite simply. KB: Yes, I agree! I remember one scene in particular - and that was when Napoleon returns to Corsica and confronts his mother for the first time and she can hardly believe it – over here it was emotional - in America they laughed; that was the difference. The two versions ran side by side in a way, but then Coppola – or Robert Harris as distributor – bought the rights from Claude Lelouch, who had been middle man, producer on this version that Gance had been inspired to make, and on Bonaparte and the Revolution. That was that - so it became more and more difficult to show the film. ML: There were too many cooks spoiling the broth essentially? | |

AND A FRENCH VERSION?! | |

French

"Napoleon" poster seen on the internet French

"Napoleon" poster seen on the internetKB: Yes, there was a girl selling T-shirts at the Edinburgh show in 1983 and she made the mistake of going in. She decided she was going to do a French version and she went to Cinémathèque: she was very upper class and authoritative, and they paid her to go through all the material they had and do a new version. By this time I had been to the Cinémathèque too and I had got a lot more in the picture. But she decided to do the version with French titles, but, she did what Gance had done in the short version, she had replaced the double storm with a triptych of the double storm - found a bloke who had been there when it was shown, so now we are on widescreen again My feeling is that it must have been wonderful for the short version but for the long version you cannot end the part there - you cannot have an interval – I thought it totally wrong to go back to the small screen after you had just had a dose of triptych, but she thought you could, and this production was given a new score by the French at enormous expense because they did not want this English connection at the time, and in Carl Davis’s case, American! ML: Even worse! KB: Even worse. Honegger | |

Honnegar | |

|

KB: So they got Marius Constant to put the works of [Arthur] Honegger

over the picture. Honegger wrote the original score but he only wrote twenty minutes of it. The rest of it was Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven like the Carl Davis score; it apparently does not fit. I have never brought myself to watch the picture with that score but apparently it kills it stone dead; it is out of sympathy: the music is just there, but it does not fit, it is not written to fit, except for the bits that were written for the film. So that is a great tragedy. People get creative as soon as they get their hands on this picture, they want to remake it. So now the French eventually get the rights from Lelouch, so the French are safe, but we have the problem in that we are restricted really to the UK. | |

Napoleon Tourists | |

|

ML: I think you are going to have "Napoleon" tourists coming from– the

travel agencies arranging flights from Australia, from all over the

world, Canada, etc. KB: It is true we had them in 2004, 2001 but then the 2004 show which was the last time we showed it in this country. We had people from all over the world – which is exactly that – very exciting. That is the third restoration and we have completely reshot every title within the font of the original - so the lettering is identical; we tinted it the proper way – the old fashioned way – so that the tints which were not in the old version are all the way through this. And we found more material; keep finding more material - some still waiting to go in – but I do not know whether you have seen my interview with Gance, but he says that as soon as he saw the effect of the triptych he lost interest in normal cinema; he said here is a new alphabet for the cinema. In fact I ought to show you that, oughtn’t I ? It is only a short interview – he says that – but it is quite important for your publication – In70mm.com. ML: The technical aspects – using ivory for the Iris, the Wollensak lens – one of the most stunning aspects of the thing is the ‘Bal des Victimes’ where it is shimmering – you have this fantastic shimmering image in front of your eyes and a ninety piece symphony orchestra, and the whole thing is so overwhelming! KB: Forty piece! ML: It feels, and sounds like more – certainly looked pretty big from where I was sitting! ML: At that time Coppola was bombarding the BFI with writs - or rather his lawyers were. KB: Yes, well that is true - but we must not talk about that. ML: It is all blood under the bridge really? KB: Yes, they get very upset as you can imagine. ML: Can we toast Mr Copolla with some of his excellent wine; his Directors’ Cut wine for finally agreeing to carry on. KB: If we get anywhere with it. ML: Fingers crossed. | |

The Brachyscope ? | |

|

ML: The lenses – using a reverse macro lens for close ups – long shots –

all this sort of thing. KB: Yes, the Brachyscope - the extreme wide angle lens. ML: This is before "Metropolis"? KB: No "Metropolis" came out in ‘26 - he was still working on "Napoleon". | |

“PRIMORDIALE”! | |

Kevin

Brownlow's projection and rewind facility. Image by Mark Lyndon Kevin

Brownlow's projection and rewind facility. Image by Mark LyndonKB: I have not seen any reference to "Metropolis" because Gance kept his notes and he used to write “Primordiale!” whatever that means and then underneath “I must have the Art Director of the Golem” – and then he would say “Primordiale! Nosferatu!” and he had to take scenes from Murnau– and then he goes to Griffiths and sees “America” – and notes – all sorts - nothing on Lang or "Metropolis". Which is very odd because he is usually very straight about his influences – and oddly enough one of his influences is [Cecil B.] DeMille – not so much in this as in his earlier films he was absolutely pole-axed by “The Cheat” in 1915 – at the time he made his pictures they looked like “The Cheat”. | |

A new alphabet for the cinema | |

Kevin

Brownlow & Abel Gance lecturing in Berlin, February 2009. Image by

Thomas Hauerslev Kevin

Brownlow & Abel Gance lecturing in Berlin, February 2009. Image by

Thomas HauerslevA new alphabet for the cinema Kevin Brownlow & Abel Gance lecturing in Berlin, February 2009. Image by Thomas Hauerslev At this point Kevin Brownlow decided to give Gance the last word and showed me an excerpt from his documentary in which Gance proclaimed what was probably historically the first manifesto devoted to large format cinema. “I felt that in a certain sense I lacked scale and that the existing “Image” was too small for me. The time had come for an enormous panorama. Here was a new alphabet for the cinema.” The Polyvision triptych system was explained. Henri Chretien was inspired to develop the anamorphic lens after seeing "Napoleon". However, the industry was not ready for it until the Americans rediscovered it. And the rest, as they say, .....! Intermission Pause Kevin Brownlow Interview - Part 2 | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |